Egosystems and Main-Man Syndrome

How Liverpool’s Rivals Bought High-Paid Problems, Not Smart Solutions

This free article is also on the main TTT website, and as ever, commenting is only on there (not here), and is for paid subscribers only.

It wasn’t the best end to the weekend with Liverpool twice surrendering a lead in a frantic and at times incomprehensibly messy match, but also one of great excitement. But despite a fixture list that wasn’t the toughest on paper, to be unbeaten, winning 66% of games and scoring loads of goals – to lead the table by a clear point – is about as good as we could have hoped for at the start of the season, even if it was galling to not get the three points at a rocking Brentford (that may not be easy for other big clubs to visit).

For all the glitzy signings made by other clubs, this season is following the path of 2019/20, when the Reds unity, squad cohesion, team interplay and understanding, meant no new signings were required to break almost all of the records. So far, bar 90 minutes from the hugely promising Ibrahima Konaté, the same pattern is emerging, albeit with the record at 100% up to the 9th game that year. City sat second, as now, but five points behind, instead of one.

There’s also no doubt that the league feels stronger this season, but this squad is still, for me, the best the Reds have ever had. Andy Robertson is off form (maybe worn out from four seasons of constant football for Liverpool and Scotland), but there’s now Kostas Tsimikas, who has a wand of a left foot. There are four outstanding centre-backs, plus an amazing fifth choice in Nat Phillips – but three are working their way back to full match fitness, and the other is adapting to life in England.

The midfield pool is deep, but obviously already racking up injuries; the worst of which was from a red-card tackle, which was the problem last season for Virgil van Dijk and Thiago. (You can’t do much about such frequent bad tackles, other than to hope the officials crack down on them.)

And the terrific trident up front has become a fab four, with Divock Origi and Taki Minamino the types of backups who rarely get a run of games to get into any rhythm, but who are capable of shining when they do get enough game time; their issue is how rarely the others are injured. (And that’s a good thing.)

This squad is better than 2019/20 (the only key player lost is Gini Wijnaldum, now a barely-used sub at PSG but on £300,000 a week), but the squad, due to terrible luck, has already lost the energy-boosting Harvey Elliott, who was really adding a new dimension on the right with Mo Salah and Trent Alexander-Arnold, and somehow already looking every inch Wijnaldum’s equal at just 18.

And Curtis Jones, at 20, is a potential future superstar, with real maturity being added to his game (he seems to be growing up fast as a man as well as a player), in addition to a touch more strength and pace as he leaves his teen years well behind. Kaide Gordon, just 16 and soon to turn 17, could also be at those levels by the spring of 2022, albeit after what happened to Elliott (against Burnley and Leeds), he’ll need protection from 15-stone thugs. He’s yet another elite age-group player.

In addition to Elliott, Jones, Minamino, Konaté and Tsimikas, the duo of Thiago and Diogo Jota are newer members of a squad that also includes the fast-improving Caoimhin Kelleher as backup keeper. The squad is deeper, and there are more options than in 2019/20. The XI remains strong, and the backups are now stronger.

The difference is that the lowering of FFP regulations has allowed the petrodollar-doped rivals to buy beyond “fair” means, and Liverpool cannot compete at that game, with the funding this year mostly going into a dozen pay-rises, with more to follow.

The rivals do feel stronger, but Liverpool cannot buy superstars they cannot afford, just as I can’t afford to buy a Ferrari just because my neighbour buys one (albeit a posh car around my way is a 10-year-old BMW, and I drive a 13-year-old Ford – when there’s petrol).

There have been some sensible signings by rivals, but also some moments of real vanity.

It wasn’t the best end to the weekend with Liverpool twice surrendering a lead in a frantic and at times incomprehensibly messy match, but also one of great excitement. But despite a fixture list that wasn’t the toughest on paper, to be unbeaten, winning 66% of games and scoring loads of goals – to lead the table by a clear point – is about as good as we could have hoped for at the start of the season, even if it was galling to not get the three points at a rocking Brentford (that may not be easy for other big clubs to visit).

For all the glitzy signings made by other clubs, this season is following the path of 2019/20, when the Reds unity, squad cohesion, team interplay and understanding, meant no new signings were required to break almost all of the records. So far, bar 90 minutes from the hugely promising Ibrahima Konaté, the same pattern is emerging, albeit with the record at 100% up to the 9th game that year. City sat second, as now, but five points behind, instead of one.

There’s also no doubt that the league feels stronger this season, but this squad is still, for me, the best the Reds have ever had. Andy Robertson is off form (maybe worn out from four seasons of constant football for Liverpool and Scotland), but there’s now Kostas Tsimikas, who has a wand of a left foot. There are four outstanding centre-backs, plus an amazing fifth choice in Nat Phillips – but three are working their way back to full match fitness, and the other is adapting to life in England.

The midfield pool is deep, but obviously already racking up injuries; the worst of which was from a red-card tackle, which was the problem last season for Virgil van Dijk and Thiago. (You can’t do much about such frequent bad tackles, other than to hope the officials crack down on them.)

And the terrific trident up front has become a fab four, with Divock Origi and Taki Minamino the types of backups who rarely get a run of games to get into any rhythm, but who are capable of shining when they do get enough game time; their issue is how rarely the others are injured. (And that’s a good thing.)

This squad is better than 2019/20 (the only key player lost is Gini Wijnaldum, now a barely-used sub at PSG but on £300,000 a week), but the squad, due to terrible luck, has already lost the energy-boosting Harvey Elliott, who was really adding a new dimension on the right with Mo Salah and Trent Alexander-Arnold, and somehow already looking every inch Wijnaldum’s equal at just 18.

And Curtis Jones, at 20, is a potential future superstar, with real maturity being added to his game (he seems to be growing up fast as a man as well as a player), in addition to a touch more strength and pace as he leaves his teen years well behind. Kaide Gordon, just 16 and soon to turn 17, could also be at those levels by the spring of 2022, albeit after what happened to Elliott (against Burnley and Leeds), he’ll need protection from 15-stone thugs. He’s yet another elite age-group player.

In addition to Elliott, Jones, Minamino, Konaté and Tsimikas, the duo of Thiago and Diogo Jota are newer members of a squad that also includes the fast-improving Caoimhin Kelleher as backup keeper. The squad is deeper, and there are more options than in 2019/20. The XI remains strong, and the backups are now stronger.

The difference is that the lowering of FFP regulations has allowed the petrodollar-doped rivals to buy beyond “fair” means, and Liverpool cannot compete at that game, with the funding this year mostly going into a dozen pay-rises, with more to follow.

The rivals do feel stronger, but Liverpool cannot buy superstars they cannot afford, just as I can’t afford to buy a Ferrari just because my neighbour buys one (albeit a posh car around my way is a 10-year-old BMW, and I drive a 13-year-old Ford – when there’s petrol).

There have been some sensible signings by rivals, but also some moments of real vanity.

Egotists

The one thing I often talk about when buying a player is the potential of what can be lost, as well as gained.

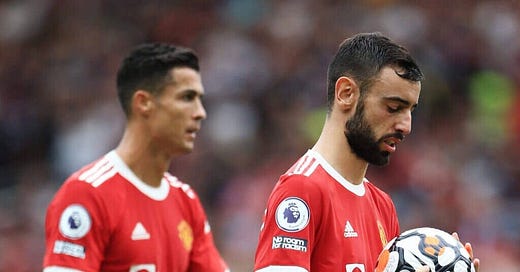

When Manchester United signed Cristiano Ronaldo, I expected him to score goals, but what would they lose by introducing a player who was in the bottom 1% for work-rate by strikers in Europe? Would Ronaldo take so many shots from poor positions because that’s what he does? How do you quantify all the good chances you don’t create because someone else keeps shooting from 30 yards, or because he does no pressing?

How would the previous go-to men feel, when usurped? Has his arrival turned Bruno Fernandes, banging in the goals and the penalties (a hat-trick on the opening day, before Ronaldo returned), into a goal-shy penalty-misser? It may be that, in time, Fernandes is actually more inspired by the presence of his legendary compatriot, but initially it seems that he might be overawed, or reduced to playing second-fiddle. It’s not that it’s a problem that cannot be solved; but it does appear to be an additional problem in need of solving. If Ronaldo’s presence ends up diminishing Fernandes, couldn’t that prove to be a bad thing?

I wouldn’t write off Man United after three defeats in 10 days, and Ronaldo is still a goal machine; and Fernandes may regain his mojo. They have an enormous squad, that cost the most money to assemble when adjusted for inflation. (Just ahead of Man City, at an average £XI of over £700m, with Liverpool and Chelsea about £300m behind, and Arsenal and Spurs another £100m back, followed by Everton.)

But at some point soon that goal machine has to start developing rust, and then what? How is a player so famous he’s almost as big as the club (and clearly bigger than the manager) allowed to be phased out? The move is a gamble, in terms of the knock-on effects. Ronaldo is nearly 37, and who will bench him when he’s 38? What happens when the entire centre of attention starts to lose his mojo and finally melt?

Steven Gerrard had a great penultimate season at Liverpool – as he raged at the dying of the light – but his final season a year later was full of acrimony, fading power and 6-1 defeats to Stoke (okay, there was just one of those, but that was one too many for this lifetime).

Then there’s the priceless – or should that be costly? – farce of James Rodriguez at Everton.

Signed to win the 2020 transfer window, he arrived at a club he didn’t even want to play for – he admitted that he only wanted to play for the manager – to earn more per week than any of the Liverpool side who’d just been crowned champions (on the back of also winning the Champions League 12 months earlier).

Andros Townsend, as a free transfer, already looks like better business; as does Demarai Gray, for peanuts. Neither would win you the transfer window; but they do look good business in the early days of this season. (I’m trying to mix my abiding affection for Rafa Benítez with a desire to not see him do too well.) As soon as Everton stop the churn of expensive signings (by their standards) and stop trying to win the transfer window they look half-decent.

In a very interesting Athletic article on Rodriguez, Patrick Boyland explains all that went wrong with the Colombian, but the author makes at least two utterly bizarre, wistful mentions of the poor Everton fans who never got to see Rodriguez in the flesh, as if it was Diego Maradona being discussed (or even an Everton legend, like Kevin Sheedy; or a current-day dedicated servant like Seamus Coleman – why would you want to see some feckless wastrel who never really displayed his talents for more than a game or two? Do some Man United fans pine over never having seen Alexis Sanchez in their colours? Do we mourn the fact that we never got to see World Cup-winner Bernard Diomède, although I was there for his overhead kick that hit the bar in one of his four games).

“That those fans never got to see him in the flesh is the greatest shame of all — Rodriguez’s move to Qatar is a sorry next step for a player who once had the world at his feet.”

Weird.

I love the story of Rodriguez at Everton (especially as it didn’t happen at our club), as it sums up almost everything that’s wrong with modern football: the transfer as form of dick-swinging; the player, whose move is overseen by super-agents, who is only there for the money, and who gets much more of it than the honest pros who work for the team and the club; the player who initially wows his teammates in training, only to soon be considered invisible, as if they feel they are playing games with 10 men when he’s strolling about; the player who has a great first month and then goes missing when the temperature drops below 20º C; the player who just takes a game off, as he can’t be arsed; the player disappearing on a private jet before the end of the season; the player as status symbol, not squad member and team player. And then the player given away, to get his £250,000-a-week wages off the bill as the club panics to meet even relaxed FFP standards after years of vanity purchasing.

I’ve spoken at length about the importance of the ‘egosystem’ at Liverpool – the unquantifiable gains made when everyone is on the same wavelength, pulling in the same direction. And in fairness to Benítez, he is trying to do the same at Everton, with low-key buys who will give him honest endeavour. But he is doing so from a position of undoing an unholy mess of status-symbol transfers.

It’s why someone like Jürgen Klopp will say to anyone who wants to leave “there’s the door” (if your transfer value is met), because unity trumps individualism, and anyone who no longer sees themselves as part of the group is like an infectious wretch capable of passing on that viral disaffection. Obviously Klopp will speak to a player and try to resolve any simple problems, but he won’t indulge them or pander to fragile egos. If they badly want out, then keeping them can become toxic.

It’s why Klopp – unhappy with the increasingly moody Brazilian winger in late 2017 – cut the ties with Philippe Coutinho midseason; the club taking the £142m as fans went absolutely apeshit about how reckless FSG were (yawn), and how the club would never win the league or the Champions League with such a policy. Yet Klopp did not want to keep a sulking player who could start to drag down the mood of others.

Well, what’s happened since, for both Liverpool and Coutinho? Liverpool banked £142m, which paid for van Dijk and Alisson, then reached the Champions League final, won the next Champions League final, and won the title; Coutinho was mocked in Spain, sent to Germany, and has picked up a couple of league titles by dint of just being present rather than any meaningful contributions (and played just twice for Brazil since 2019).

Barcelona – obsessed with superstar signings, all of whom tanked – are now €1.2billion in debt. Meanwhile, clubs that tried to spend their way into the Premier League are going bankrupt. The Championship is like one giant Ponzi scheme, waiting for the cards to fall.

Hubris

But I’ve also seen hubris and vanity turn Spurs from incredible overachievers on a relative small budget who ran the Reds close to the Champions League in 2019 (and went close in league title races) to succumb to a succession of dumbass big-dick decisions.

First they ditched their elite manager, and – as I called it at the time – replaced him with a man who played the wrong style of football for the squad. He was appointed on the outdated basis that he was a “winner”.

I loathe the concept of the “winner” as a constant quality in a manager, because Brian Clough was an incredible winner in the 1970s and then not-much-of-a-winner in the 1980s, and a total loser by the 1990s.

Arsène Wenger won with the best football imaginable between 1997 and 2004, and then – like Clough – went from title-winner to trying to hoover up a domestic cup or two (which I don’t count as being a winner; otherwise Juande Ramos would have a statue at Spurs). George Graham won two titles with Arsenal around the turn of the 1990s, then slipped into obscurity, via some stuffed brown envelopes.

Howard Kendall was just one of several managers who returned at least three times to manage the same club, and almost all of them saw a big drop in their win percentage every successive time they took charge. (And Kenny Dalglish’s second stint at Liverpool was far worse than his first, albeit I still back the decision, as the need was for him to be better than Roy Hodgson to rescue 2010/11, and that was achieved. I don’t think we expected miracles.)

All of these men were absolute winners. Until they couldn’t win as often anymore.

Arrigo Sacchi returned to AC Milan having won everything, and second time won only 28% of his games. Fabio Capello went from being like Bob Paisley in his first spell at AC Milan to being more like Roy Hodgson in his second. (The classic 36% win rate.)

Radomir ‘Raddy’ Antić had three spells at Atlético Madrid in quick succession, and each time, like Sacchi, he halved his win percentage: from 51% to 28% to 13%. One more go and it would have been 6%. A rare exception is Jupp Heynckes, who always did well at Bayern, albeit Bayern have a monopoly on the Bundesliga. Any club who finishes 2nd can be certain that Bayern will simply nab their best players. How is that “fair”?

(It’s ‘funny’, shall we say, that Bayern and PSG were two of the only big clubs to oppose the European Super League, when they have won 17 of the last 20 combined titles in Germany and France, and are likely to make it 19 from 22 this season. They have no insecurity about qualifying for the Champions League as they don’t really even have much when it comes to winning their own league. Now PSG – backed by Qatari-based financial doping – have gained more control of the club scene in Europe, too. None of which is to say the ESL was an idea I would back, but equally, it remains an idea that was blown out of the water in the usual red-faced online outrage before its merits could even be discussed. Football is broken in so many ways, and as with anything that’s broken, you need to discuss all the potential fixes – not simply justify continuing on the same path when it’s leading to chaos. But I digress.…)

And while Mourinho won the title in his second stint at Chelsea, it was a far less successful spell overall, and soon he looked to be on the Clough and Wenger train from title-contender to League Cup aspirant. (Spurs sacked him days before he could have won one for them, which seems odd, if he was such a winner; and at least winning the League Cup was something he remained good at.)

Five years is a long time in football, given how the game changes. Managers don’t lose all their skills (or knowledge) overnight, but the game can evolve to make some of their cutting edge abilities seem a little old school. Every year that a manager ages also takes him a year further away from the players he must inspire. Mourinho – greying and grumpy – was a nightmare waiting to happen, and whenever he leaves a club it’s usually in a mess.

I’d already noted down that Spurs’ new stadium feels more like a vanity project, given the incredible debt involved (although long-term it may prove a wise move, if it doesn’t sink them first), when I read that Phil McNulty noted in a piece today that:

“Mourinho appeared very much a quick fix, Levy-led vanity project that was an expensive failure.”

Vanity stadium. Vanity appointment, followed by a sacking with no plan (days before a domestic cup final), and a recruitment botch-job where Nuno (who did well at Wolves, albeit with about a dozen compatriots who would buy into his ideas) was like the chubby kid with two left feet who gets picked last for a kickabout. Spurs ran out of alternatives.

I also saw it as offensive to the Spurs fans that their Argentine and Colombian players preferred to go off and abandon their club and accept 10 days quarantining in Croatia when the rest of the league (bar Aston Villa) had accepted, as one, that it wasn’t fair to take their wages and be unavailable for their clubs after the last international break. Without them, Spurs duly lost 3-0 at Crystal Palace. I can’t express how disrespectful that is to the fans whose costly season ticket and hefty television subscriptions pay their wages. International football is important to players, and that’s fair enough; but the clubs and those fans pay their wages. It stinks of mercenaries, not really wanting to be there. Where’s the unity?

Then there’s the star player who wants out. Without Harry Kane, Spurs beat Man City and won away at Wolves. They unified. With him returning to the team, they’ve won one league game and lost three, to a goal difference of 2-9 (and Kane scored neither of those two goals).

Yesterday, Arsenal twice scored soon after Kane took (or tried to take) an utterly stupid shot from a ludicrous distance instead of passing to his teammates. When, on the second occasion (as he miskicked), he at least chased back to redeem himself – and then slid the ball perfectly for an assist to Arsenal (and it’s nice to see the brilliant Bukayo Saka having such a good time after the Euros; kudos to Kane for setting him up).

Kane looked moody, selfish and like a man dragging a team down with him, as they rank 20th out of 20 for distance covered.

I keep hearing that he’s the “consummate professional”, but I’m not sure his behaviour this summer was anything other than a bit shitty, even if a lot of players do it. Going on strike is hardly the sign of an ultimate pro, even if it what a lot do to force through a move that breaks their contract.

Then there’s the vanity signing of Tanguy Ndombele, for a fee of up to £65m, for a talented player who appears to have the heart and desire of an ageing diabetic field mouse.

Cohesion

I guess this is just a way to say that cohesion is more important than anything else in football. That talent is involved is a given, because all players have talent. Hunger, unity, work-rate, commitment, wavelength-understanding (which increases with time spent training and playing together), respect for your colleagues – all of these make a team.

Liverpool, under Klopp, are all about being a team. They are not about individuals, and for all the lack of big-money buys this summer, the strengths are all still there.

Mo Salah is the biggest star, but he tracks back to defend in the full-back positions, and runs his chunky socks off. He is the main man, but not put on a pedestal and worshipped; he is part of the team, working hard for everyone else. If all these players stay fit, and give their all, the Reds stand a chance, even with FFP now favouring those who prop up clubs with oil-based wealth.

It’s a question of being a combined force, to exceed the sum of the parts.

As the famous poem states:

Though much is taken, much abides; and though

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are,

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson*