Liverpool FC’s “FSG Boy” – My Life As A Shameless Apologist

I try to insulate myself from idiots these days. But there are different types of idiots, of course. I’m trying to not label the uneducated or the ignorant as idiots per se; especially as, say, a group of people with certain views may just be getting bad information, or be caught in a bad filter bubble, or consume an unreliable media diet. As someone who has had not three but four vaccinations since the spring (three Covid, one flu, to the point where my upper arm felt like it had gone four rounds with Mike Tyson), I can still understand why someone may be fearful of vaccinations, without me thinking those people evil, deranged or even idiots (whilst acknowledging that there will indeed be some prime fuckwits within those ranks, just as there are in lots of large groups).

There’s a certain kind of idiot who I can call an idiot, however, and that’s someone who acts as an idiot towards me.

There’s no point me engaging these people directly as it’s not worth the time and effort to be talked past. Of course, they probably won’t read what I write in article form (such as this), but at least I can make a case without constant interruption or pithy insults. Maybe some will see sense, or at least come in from the extremes.

Given what little good can come of it overall (despite some individually interesting comments), I don’t often read many replies on social media, in part as I spend as little time on social media. When I do use Twitter these days, I can’t even see replies by ‘egg’ accounts. (As such, I can forget such people still exist.) However, I did get this direct message on Instagram, which made me laugh, and also, reminded me of the crazy world in which we live.

First, being called a ‘boy’ at 50 is quite amusing. Thank you, my friend!

(And as for being lazy … well, read on, if you can handle it, sunshine.)

It’s yet another example of this alarming extremism within the Liverpool fanbase that thinks everything FSG do is evil, and everything that goes wrong at Liverpool is FSG’s fault.

I saw this when Harvey Elliott had his ankle broken by a 6’3” centre-back launching two-footed into the young lad. That was FSG’s fault, for not investing more in the team in the summer. Well, what if it was Jack Grealish (not that he seems the kind of person to fit in at Liverpool) on the end of that? £100m, but in hospital?

Indeed, I argued at the time that Elliott’s early-season brilliance was actually a positive from the FSG model, of finding undervalued assets; in this case, a player playing like a £50m attacking midfielder having just turned 18, but who had his ankle dislocated and his leg broken by the challenge. (Having just played 42 games in the brutal 2nd tier and come through it unscathed.)

Now, that’s not to say that FSG get everything right. They’ve got plenty wrong, as I’ve said all along. But people, high on their own Dunning-Kruger fumes, don’t seem to understand how a football club is run, and cannot then analyse the balancing that needs to take place. Arguments about net spend are the kind of thing I moved on from in the 2000s.

Now, if you want Liverpool to be run by corrupt foreign states with limitless money, then we can’t really have a discussion. There’s no common ground.

If you want a Roman Abramovich (almost as oily), then we’re talking about a man who is now owed £1.5bn by Chelsea, which seems an unrealistic aim. Abramovich arrived before FFP was introduced (FSG arrived after), but to expect a benefactor like that is not realistic. Or, if it becomes the only way, then football is done, anyway. (As a sport, at least.)

Newcastle have just got theirs, but really, do you want that? Do you want football trophies that are bought – and if so, are you the kind of person who goes to the trophy shop to buy a plastic “World Champion” statue engraved with your name for £30?

You can hate FSG all you want, but let’s look at the reality.

In the summer, after Covid cost the club a ton of money and a ton of momentum (where momentum, a streaky concept, was genuinely upset by the disruption), the priority, with the money the club earned, was to reinvest all that money in new deals and wage rises for up to 15 players. As it was, 11 got done. Some remain ongoing, with costlier figures involved.

Harvey Elliott, Trent Alexander-Arnold, Fabinho, Alisson, Virgil van Dijk, Andrew Robertson and Jordan Henderson were vital sign-ups. Adrian, Caoimhín Kelleher, Nathaniel Phillips and Rhys Williams were less vital, although Kelleher was arguably crucial too, as the best 2nd-choice the club has had in years, with potential to be world-class and maybe even usurp Alisson in a few years. Mo Salah would obviously be the big one, but it’s also the most complicated one, for various reasons I’ve outlined all season long.

Indeed, to look at how well FSG have done, certainly since 2012 – when Ian Graham and Michael Edwards led the behind-the-scenes revolution, with help from Mike Gordon – you possibly just have to contrast their actions with what Man United have done, with owners who take fortunes from the club each season.

The Super League aside, a generally unsavoury idea for which both sets of owners were guilty (albeit the need for a kind of Super League may become apparent in time, given football’s myriad financial problems), let’s refer to a few things that Man United’s owners and key operators have done in the last few years, which can in part be seen in a new Athletic article lamenting the current mess.

The reason I want to contrast with United is that United – away from the boardroom, at least – have actually done pretty much what their most fervent transfer-craving fans would have wanted.

They spent what would now work out, with football inflation, as £147.8m on Paul Pogba, bringing him in on huge wages. To see off rivals, they then bought Alexis Sanchez, and paid him even more than Pogba, and many times more than they were then paying their best player, David de Gea.

Their wage structure spiralled into madness.

Just when they stabilised things and appeared to moving forward with a younger team (and a mediocre manager), they brought in a non-pressing 37-year-old superstar on more than half a million pounds a week, again to stop him going to a rival.

Sanchez won that January transfer window for United. Pogba surely won the summer 2016 transfer window for them. Ronaldo won the 2021 transfer window for them. But that’s the only thing of any meaning they’ve won in that time. And indeed, it’s of course, of no real meaning at all. By contrast, Diogo Jota was a bit underwhelming to many observers, as had been Mo Salah, Sadio Mané, Andy Robertson, Roberto Firmino and many others.

Liverpool do not win transfer windows. But they have won the league (after a 30 year wait) and the Champions League, and been a whisker away from doubling those tallies, in just the past four years. Barring injury crises and Covid outbreaks (last winter, this winter), they might have challenged for even more, but Liverpool were nearly wound up in 2010, and the club had sold some its best players without replacing them before FSG took over, with Roy Hodgson in charge and the Reds, having failed to qualify for the Champions League, down in the relegation zone.

I will go on to contrast Liverpool now with Liverpool then, which is perhaps the comparison that matters most; but the situation at United shows how throwing money at problems can, if done badly, create more problems than solutions.

Again, United had a good season in 2020/21, without ever looking like title-winners. They started this season looking like they could perhaps challenge (most pundits favoured them over Liverpool, remember).

Then they signed Ronaldo – oh how their fans rejoiced! – and while they have fallen from 2nd last season to 7th currently this term, they were top when Ronaldo arrived (seven points from the first three games), and their form with him in the side is that of a mid-table team. But wow, he really did seal the winning of the transfer window.

A great but fading individual talent absolutely exploded that dressing-room harmony, by unbalancing everything – just as he does on the pitch. His outrageous, almost otherworldly superstardom seems to mean he has to play every minute of every game, despite being closer to 40 than 30. While there are countless other issues with United, that one giant issue seemed to tip team unity into team disharmony. Even now they’re still trying to work out how to build a team around him, as his arrival likely costs them a place in the Champions League.

The aforementioned article provides an insight into how hard it must be to manage the squad at United, who kept buying without selling, and who kept destroying unity by handing out the biggest wages to often the least-deserving players (either in terms of performances or work-rate).

“At times, [Ralf] Rangnick has taken training for 26 players — there are 29 senior professionals on United’s books, not including the seven out on loan — and he is said to have found motivating them all difficult at times, given in each game almost a third will not be involved.

“Eric Bailly had not made more than 13 appearances in a Premier League campaign for four seasons before last summer being awarded a new contract to 2024 with the option of a further year. Juan Mata made 10 starts in all competitions in 2020-21 but got a year’s extension. Phil Jones had played 69 Premier League games across four campaigns at the time of getting a fresh four-year contract, which could extend to 2024.”

A bloated squad replete with overpaid players is a recipe for a disaster. A superstar who is so much more famous and feted than the rest of the team is also often a destabilising issue.

I wrote 18 months ago about the general problem in an article called ‘The Toxic Rot of the Unhappy Superstar And How It’s Not An Issue For Klopp’s Liverpool’, and all of that seemed to apply when United re-signed Ronaldo. In general, it’s bad enough when the player is at his peak, but once melting, the frustrations with his own performances will grow, and spread; he’ll get angry with team-mates, who will shrink in his presence. Factions will arise. It’s textbook.

Denying Reality

The idea that FSG are not “investing “in Liverpool is just plain wrong. You can argue that you want them to invest more of their personal money, but that was never the promise, and football was supposed to be moving towards Financial Fair Play, not financial doping. Clubs were supposed to be self-sustaining, not plumped up by personal dosh.

The Main Stand has been rebuilt; the Anfield Road end is being rebuilt; and there’s a new state-of-the-art training ground. This has been done with some low-interest loans from FSG, but mainly by improving the club in all areas, so that the club can then, in return, be improved further by the financial rewards: a virtuous cycle. That was always the idea. If you don’t like that idea, then that’s your problem. If that idea is not suited to 2022, then that’s football’s problem.

Just as they ended an 86-year wait for the championship with the Red Sox (and won many more), the 30-year-wait was ended at Liverpool, with many other great seasons since 2013 thrown in (and a couple of duff ones, but that’s not bad in an eight-year period). Again, FSG inherited a team that had been underfunded by the previous owners who, unlike FSG, acquired the club in a leveraged buyout, with money they did not therefore have.

Liverpool were a shambles on and off the field by October 2010, with an ill-suited manager, a squad full of deadwood and makeweights, and no football knowledge behind the scenes: just bankers and moneymen in Cuban heels. The club had a future as bright as the Titanic’s, it seemed.

You cannot base any analysis of the ownership without the fact that it was a rapidly sinking ship, and that it could take years to a) fix the repairs just to re-float it, and b) turn the ship around.

If you cannot remember the state of the club, go back and do some research; especially if you were too young, or are too new to following the Reds.

It really was the lowest point, by far, of any time since Bill Shankly turned up to an amateurish mess in 1959 (a year that’s most worthy of a song). From 1963 until 1990, the club was flying.

Liverpool had periods of poor seasons and substandard managers between 1991 and 2010. But even when Graeme Souness took over an ageing squad (that grew a bit too old after the aftermath of Hillsborough made it harder for Kenny Dalglish to overhaul the wonderful team he’d assembled), Souness was still able to pay British-record fees. Liverpool were still a rich red giant.

Even when clearing up the countless costly mistakes, duds and ‘decent at best’ whose combined cost would equate to hundreds of millions in today’s money (Paul Stewart, Dean Saunders, Nigel Clough, Neil Ruddock, Michael Thomas, Julian Dicks, et al), Roy Evans could still break the British transfer record for defenders (twice) in 1994, and in 1995, the British record outright on Stan Collymore; and there was a particularly gifted group of local youngsters in the side, whose emergence was in part a byproduct of the failures of the big signings.

By contrast, 2010 saw the team full of some less-expensive (but some highly-paid) stars, with some of the few gems sold to pay off debts. The club was financially screwed, and close to administration.

Liverpool had the costliest squad, adjusted for inflation, at times in the 1990s, but by the turn of the millennium they’d fallen well behind Man United, and Chelsea were about to get an injection of £1.5bn (that, adjusted for football inflation, would probably be at least twice that amount, given how much of that came between 2003 and 2010).

In 2010/11, even after the mid-point arrival of Luis Suarez (an expensive bargain) and Andy Carroll (a very expensive flop), the Reds just about ranked 4th (narrowly ahead of Spurs and Aston Villa) in the £XI rankings, when rising from near the bottom to 6th place in the actual league table under Kenny Dalglish. But the gap to Man City (their big oil-based investment taking them upwards) and Man United saw the Reds at roughly 50% their, and Chelsea cost closer to 3x Liverpool’s £XI (with the £XI being the cost of all league lineups adjusted for inflation).

So that was the starting point: a Liverpool team that cost just 1/3rd of what was then the reigning champions’ £XI, at a time when Man City’s arrival on the scene made it that bit harder to get into the top four (now that there was one new rich team on the block; while Arsenal, at that stage, were still on a long unbroken run of top-four finishes, the like of which seems a distant memory now, after top-four finishes became so passé.)

FSG inherited a team outside of the top four, with Spurs also blocking the path and Aston Villa on a virtual financial par. That’s the reality.

Fast Forward to 2022

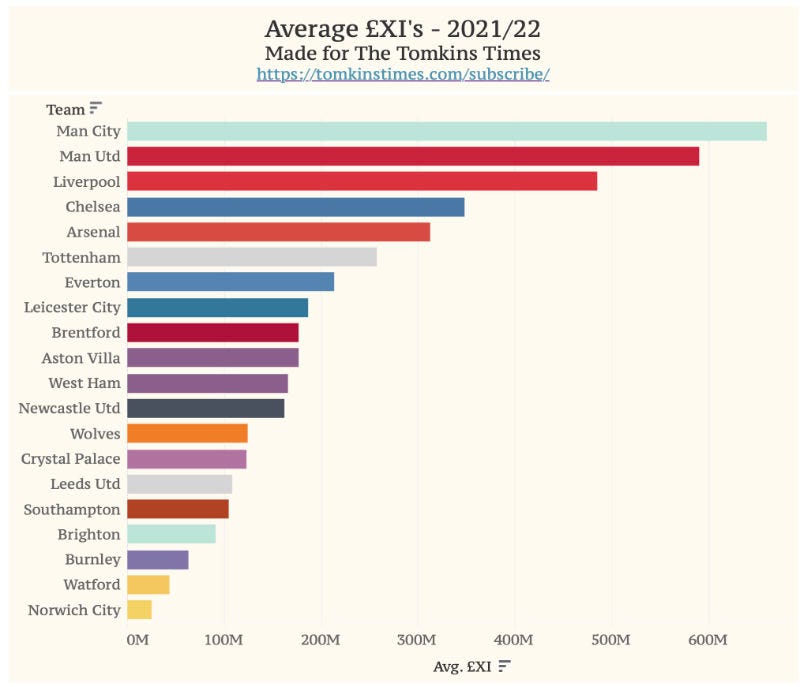

Despite low “net spends” that so enrage some fans, the money the club has generated can be seen in its current wage bill and its £XI.

Liverpool currently rank 3rd on £XI, with the gap to the top “only” double (compared to triple back in 2010), with the £XI diminished somewhat by various absentees; and have recently had the 2nd-biggest wage bill, when it would have been around 5th 12 years ago.

Now, that 2nd-biggest wage bill, as noted in accounts that are obviously out of date (all wage-bill data tends to lag a year or two behind), relied on massive bonuses, paid to the players for winning the league. So rather than the wage bill drive the winning of the league, the winning of the league half-drove the wage bill. That was clever thinking: don’t promise the players fortunes, but promise them a lot of money if they earn it with performances. If the performances are poor, the wage bill is lower, because the income will be lower.

But even so, we’re talking about Liverpool now in the general vicinity of the biggest clubs on wage bill, which is where the Reds’ heavier investment has gone; with the model based on underpaying for players on transfer fees (Salah, Mané, Fabinho, Jota, Robertson, et al), and offering modest wages; then rewarding performances with higher wages in bonuses and/or pay rises.

It’s eminently sensible.

Even record-signing Virgil van Dijk looked a bargain until his knee was snapped in two; his value, two years ago, far in excess of the fee paid.

(Look at the current recent £100m+ buys: Jack Grealish and Romelu Lukaku, for no great impact; and in Spain, Eden Hazard, Philippe Coutinho, Ousmane Dembélé and Antoine Griezmann, to remind yourself of how splashing £100m does not, in itself, get you anywhere.)

As often with the truth, it’s in between the extremes of “FSG are cheapskates and all the success is down to Jürgen Klopp” and “Liverpool spent a ton of money – look at van Dijk! – therefore they bought the title”.

The truth is that Liverpool have a fairly expensive team and a fairly hefty wage bill, but have achieved far more than you would expect on that budget, given that those achievements include finishing 1st in Europe and 1st in the Premier League, as well as 2nd in both, too.

It’s also true that Covid meant that clubs with sportwashing owners could invest more than FFP previously allowed, and the £100m+ lost by the Reds during lockdowns and lockouts meant the sensible, sustainable model took more of a hit. Plus, Manchester United remain a money-generating machine, if not a footballing one.

That the rise – up to March 2020, when Covid really hit – had nothing to do with FSG, as I often see said, seems bonkers to me. Again, you don’t have to like them, but let’s stick to the reality.

The success achieved since 2010 is remarkable – go on, admit it to yourself, if you’re denying it – and while a lot of that credit goes to the uniquely brilliant Jürgen Klopp, it was the structure put in place that identified Klopp as the man to appoint (at a time when his reputation had suffered a blow and others were expressing doubts), and it was that scouting and analytical infrastructure that convinced Klopp of things like buying Mo Salah, when Klopp wanted Julian Brandt.

While Klopp will have driven some buys, and been happy to agree to everyone who has arrived, he was not the one who sourced Salah, Andy Robertson, and various others. He has not worked alone, but as the key cog in a machine designed by FSG and/or the people FSG appointed to design the machine.

It was FSG who appointed Ian Graham, whose model identified Klopp as unlucky in his final year at Dortmund, and FSG who appointed Michael Edwards to oversee transfers, and it was Mike Gordon of FSG who personally convinced Klopp to join Liverpool, when the German was wanting a sabbatical (and where United’s earlier attempts to woo Klopp were as successful as a potential paramour sending a Valentine card containing a sloppy turd).

Again, do we have to be Team Klopp or Team FSG? What about Team Edwards or Team Graham or Team Gordon?

Hang on, didn’t all of them combine to move the club up from outside the top four every year but one (2009/10 to 2015) to inside the top four and challenging for big honours every year since 2016?

Not just that, but it’s been more than just scraping into 4th; it’s been 1st, 2nd and 3rd, with records points tallies and glorious European adventures. This is not me putting a spin on anything: those are the facts.

Liverpool may never again be the richest club, especially now that the wealthiest owners in football are at Newcastle, and given what City can invest. But Liverpool have become highly competitive again, from such a low position in 2010. More money goes into the team than people notice (due to wage-bills being less headline-grabbing than new signings), but it’s also not financially-doped or sportswashed to success.

I would argue that FSG have done everything they promised, and more; with some luck along the way, but also, some bad luck (Steven Gerrard’s slip was surely not their fault, nor his – just one of those things; losing a Champions League final to the underhand Real Madrid was underserved; missing out on the title with 97 points was unheard of; and a few others.) They’ve made some mistakes, but who hasn’t in the past 12 years?

And to come back to the current side, the “lack of investment” was a mirage when 11 players (most of them senior ones) got new contracts, at a time when selling players for their previous market value was difficult, should an overhaul have been desired. (Even fringe players saw their values halve.)

I stand by my assertion that the Reds did the right thing in continuing with much the same squad, with the addition of one brilliant young centre-back and the return from loan of an outstanding teenage attacker; but no matter how many players you buy, if you go into a run of three vital games without more-or-less the entire spine of your side (Spurs away, Leicester away and Chelsea away) then you are much more likely to drop points – especially if the numbers absent pass four or five and move into double figures.

Indeed, as we showed with analysis last season, Liverpool were often fine with five or six out; but struggling with ten or twelve out. That’s only natural, especially if it includes key players and their understudies.

If Liverpool had played the 2019 Champions League final without four or five key players as well as four or five backups, then the chances of winning it would have fallen sharply. A couple missing in the semi-final at Anfield was surmountable; just as the Reds remained top of the table for two months after van Dijk’s injury last season, until Joe Gomez and Joel Matip joined the season’s-over list.

No matter what you pay, your new signings come with a risk of underwhelming, either temporarily or permanently (there’s only a slight increase in the chance of success the more a transfer costs, which is why mega-squads full of expensive players spread the risk over a wider range), and any of them could be derailed by a shocking tackle.

It was not through a lack of investment in midfielders that someone like rookie Tyler Morton was thrust into a vital game at Spurs, along with other backups. Even after the exit of Gini Wijnaldum, the Reds went into the season with a ton of senior midfielders.

It was due to an injury crisis mixed with a Covid outbreak, with the two brightest and most experienced youngsters (Elliott and Curtis Jones) out with freak injuries. Had Liverpool got their festive fixtures cancelled, as other clubs did, they may still be in the title race, but they did not. You can call that mistake, or just the way the cookie crumbles, especially when you’re not trying to rig the system to get rid of unwanted games.

As such, Liverpool are stuck between not having enough money to easily compete with the Manchester clubs in the transfer market and having much more than the “we’re skint” brigade would have you believe – and so it’s perfect for a culture war, where extreme sides are taken, and everyone misses the point (and the target) in between.

Spending Analysis – A Little More Depth

To wrap up, a final section, looking at some figures.

It’s now more than 12 years since I first worked with Graeme Riley to create the Transfer Price Index, and with Graeme busier with his daytime job these days, I asked TTT stalwart Andrew Beasley to help update the database, in as similar a manner as possible.

As ever, it’s difficult to find 100% accurate transfer fees, with much more obfuscation these days. But it remains a good indicator of on-pitch resources, as explained in 2010 when we first introduced the concept.

So, for example, when Adam Crafton of The Athletic (nothing against him personally) says the following, it’s easy to pull apart the weak argument (and this is 2022, people) of one season’s net spend, which has very little bearing on what a club achieves.

“I don’t really see why Man City’s dominance this season is a cause for major consternation. Their net spend this season is £30m and they lost their best ever striker in Aguero too. It’s far more a reflection of brilliant coaching and a great mentality from staff and players.”

While it’s also true that City do have “brilliant coaching and a great mentality”, it’s also done on a budget that far outstrips those at Liverpool (and yes these days, Chelsea), and has only one pound-for-pound competitor, in Man United.

To base anything on what you spend in one summer is like saying that a £20m mansion in London “cost nothing” because no work was done on it in 2021 (ignoring the platinum-plated renovations from 2009 to 2020, and the fact that it cost £14m in 2008).

So the main thing is: how much does your team cost, adjusted for inflation? That also then factors in players who are unavailable, which wage bill analysis does not. (But of course, wage bill analysis is handy too, and City top that as well.)

As I’ve been noting for years, the £XI – the average cost of a team in a season, adjusted for inflation – is a good indicator of where a club can expect to finish. It’s not rocket science, and also, not perfect; there will always be over- and under-achievement within any model. It’s a handy shorthand for spending, give or take a few percentage points on accuracy.

And of course, Liverpool also have brilliant coaching and a great mentality, but far less money than City.

(Click here for the interactive graphic.)

That said, and as already noted, the Reds also have more money than some of the club’s own fans like to acknowledge. It’s far healthier than 2010, which I keep coming back to.

(Despite all that, Chelsea can still field a more expensive side on paper. Were they ever to field Romelu Lukaku and Kai Havertz regularly, with Jorginho and Ngolo Kante in midfield, and if Kepa retained the no.1 jersey beyond the AFCON, things would get interesting, even with Ben Chilwell out for the season. However, Chelsea’s £XI lately – for the first time since I started focusing on it after the massive investment of Roman Abramovich – is kept in check by several home-grown players. Adjusted for inflation, the most expensive £XI of the entire Premier League era still remains Chelsea’s mid-2000s vintage, before FFP slowed them down. Of course, they also invested massively over the years in their youth system, which fell outside of FFP regulations, so they were even allowed to gain an advantage there – but it’s less distasteful than just buying up all the ready-made players and seeing which ones succeed, and writing off the duds.)

Incidentally, I’ve also studied the data in the past, and found that big net spends in one season often have little effect, but that it’s the season after that often sees a big positive impact on league form – once those players have settled. But again, plenty of big signings fail. More than people think. It’s a difficult arena in which to consistently succeed, and having more money means more margin for error.

Meanwhile, as I’ve also shown, teams tend to get better the more time they spend together, as they share an understanding of how to pass, press and move in unison. Churn and high turnover is often toxic. (Again, but not always.)

As Andrew showed in his column for the Liverpool Echo, City have a big financial edge over Liverpool, just as Liverpool have a big financial edge over other teams, who will finish lower in the league.

Where the value of a pound has risen approximately 80 percent between the dawn of the Premier League and today, in transfer terms the growth has been more like 3,000 percent.

… the Liverpool starting XI [at Chelsea] cost a combined £409.3m when inflation is taken into account.

It was their second cheapest line up of the season though, with the team which took on Tottenham Hotspur – which featured four players who either came through the youth ranks or joined the club on free transfers – clocking in at £369.3m.

However, the Reds team on Sunday still cost more to assemble in TPI terms than Chelsea’s side, which set them back £361.7m.

Neither club is among the league’s paupers by any means. Both XIs which started at Stamford Bridge were in the top 68 most expensive among the 382 which have featured in the Premier League so far this season.

When you consider that Manchester City’s starting line up for their win over Arsenal cost an inflation-adjusted £796.5m though, more than Chelsea and Liverpool’s sides combined, the size of the task facing them becomes clear.

Should Liverpool win their game in hand, they’ll return to 2nd in the table. That’s above what you’d expect, which would be 3rd or 4th.

The Reds have also been outstanding in Europe this season, with the club’s best-ever group campaign (100% win-rate), in what was supposedly a group of death. Up until the Covid crisis on the day of the Spurs game, Liverpool were breaking all kinds of scoring records, and set an all-time club record for longest all-competitions unbeaten run. Hardly sounds shabby, does it? Or that it was inevitably going to fall apart.

To suggest that the club is anything other than competitive would be deluded, especially when compared to most of the seasons since 1990, the last time the club was truly dominant.

The talent is there. The togetherness and shared experience is there. What’s not been there has been

a) a lot of great players due to injury and illness, including some energetic younger stars, with it hitting “crisis” point only in the last three games; and

b) the 100% top-form of someone like van Dijk, who may never quite reach the old heights after having his knee snapped (ACLs can take a long time to recover fully from), but whose capture was, if anything, a sign that FSG will pay big money when the deal is right and the money is there (in that case, generated by the sale of Philippe Coutinho in 2018 – which was, of course, held us as a sign of FSG being irresponsible lunatics who are ruining the club).

Equally, the club will not pay over the odds for players, and will not blow the bloody doors off its wage structure to suit any single individual, even if someone has to be paid the most (and that should be Mo Salah). After all, the “no-brainer” of United bringing back Cristiano Ronaldo for a relatively small fee but on double what most of their other stars were earning should serve as a warning to what wage disparity – that less obvious cost – can do to unity.

And so, to summarise: you might not like FSG or think them pure of heart, but they are not the devil’s envoys sucking the club of money and competitiveness; and since they purchased Liverpool, the rise in the club’s stature and achievements has been consistent and long-lasting. There will be a statue of Jürgen Klopp at Anfield one day, but not John Henry, and that’s the way it should be.

At some point they may sell for a profit (which you could argue they’d have earned, but which would obviously upset a lot of fans), but for now, as at the Red Sox, they’ve taken perennial losers and, rather than flip them for a quick buck, made them into sometime-champions and frequent challengers over the long-term.

In addition, I don’t know a single Liverpool fan who, if they followed the club’s existential court case in late 2010, whilst envisaging another Roy Hodgson-led team containing Paul Konchesky, Joe Cole, David Ngog, Sotirios Kyrgiakos, Martin Kelly, Jay Spearing, Jonjo Shelvey, Milan Jovanovic and Christian Poulsen, who’d have said that wasn’t good enough for them.

You shouldn’t need to be called “FSG boy” or an apologist to point that out. (But as they say … whatever.)

As ever, I’ll discuss the article with paying TTT subscribers on the main site, which can be found here.