Man City, Liverpool & Arsenal Run-ins Analysed – Fixture Density and Intensity

The punishing pinch points of 2023/24 (Full Version)

I first previewed part of this article on my ZenDen side Substack. The email version of this article may be truncated by some email services.

In analysing all difficult runs of fixtures in the past two and a half seasons for Liverpool, Man City and Arsenal (plus Newcastle, for reasons I’ll get onto), one stands out far above all others in terms of difficulty of opposition, lack of time between games and the number of points won: Liverpool, in 2021/22, with the 12 games up to 14th May 2022. (More on that later.)

My aim, in undertaking a mini study, was to find a way to more accurately predict run-in results, even if nothing can ever be properly foreseen. With every passing year, the Premier League gets more physically demanding.

I have also looked at the full seasons (and 2023/24 to date) of some of the top teams from the past three years and found a clear pattern as to what gap between games is the most prolific, comparing three, four, five and +5 day intervals.

Also, people saying City will go on 10-20 winning streak (it must have been mentioned half a dozen times by TNT’s Darren Fletcher on a gushing commentary in the Newcastle game) ignores the incredibly intense and dense fixtures they have awaiting this season, and how they haven't been as good against better teams so far in 2023/24.

That said, they may still go on a huge winning run, of course; but we have to look at previous winning runs, to see how tough they actually were. Last season’s, for example, had an incredibly beneficial set of fixtures that they won’t have this time around.

And generally, bar Liverpool in 2021/22, there’s a point where the fixtures get so dense and intense that the ppg has to drop – as I noted in a recent piece introducing the concept, when looking at Newcastle as a starting point (to contrast last season's relative dominance, with this season’s collapse).

If City have all their best players fit and Liverpool and Arsenal do not, then that can change things. And vice versa.

A few weeks ago I listed just how many minutes Arsenal and Man City players had played this season, compared to the rested Reds (albeit injuries and suspensions added to the lower workload for some).

Since then, Arsenal have looked jaded. They’re going away for warm weather training, as are City; Liverpool are taking time off, and staying home.

Mikel Arteta is not rotating much, and that is likely to work against him, if it isn’t already.

Injuries

The one big caveat is always injury concerns, with Liverpool under Jürgen Klopp, as shown by Andrew Beasley, to have a great points per game when six or fewer players are absent, and a much poorer ppg when more are injured.

That makes total sense, as a dozen injuries leaves you with just a dozen players (normal squad sizes are around 24), who may not be the best XI (highly unlikely that you only have reserves injured), nor the most balanced XI. And their workload into the red-zone multiplies with each match.

I said this about Virgil van Dijk in 2020/21 – Liverpool were fine without him, until Joe Gomez and then, in particular, Joël Matip were injured (immediately after the 7-0 win at Crystal Palace), and then Fabinho, who was standing in.

It’s not about missing single players, which may see a slight decline in fortunes, but losing all your backups as well, which will likely lead to a big decline in fortunes.

As great as Nat Phillips and Rhys Williams did, it also took the return from injury of Diogo Jota, Thiago Alcântara and others, after months out, so that the team could be balanced enough to play two raw “stopper” giant centre-backs, whose job was merely to head everything and block everything, winning aerials at an insane rate that meant Fabinho could return to the midfield once Jordan Henderson, another stand-in centre-back, was ruled out for the season in February.

So, all the analysis in this piece is highly dependent on squad availability; but then, the more dense the schedule and the less scope for rotation, the more injuries can mount. We've known since the days of the Milan Lab that really short intervals between games increases injury rates.

Football has never been more athletic, says The Athletic.

“Football has never been more athletic.

Sprints have risen for the past three Premier League seasons. High turnovers — defined as an open-play possession beginning 40 metres or less from the opponent’s goal, a proxy of high pressing and/or counter-pressing — increased almost 24 per cent from 2018-19 to 2022-23. If this season’s current rate holds, there will be another 12 per cent rise.

More teams press, often with player-for-player approaches, which can involve centre-backs tracking strikers all the way to their own defensive third. This is possible because short build-up has become the norm. Goalkeepers have never played shorter, with just 31.3 per cent of open-play goalkeeper passes launched (classed as those kicked 40-plus yards) this season; that proportion was 48.4 per cent in 2018-19.

A 2020 paper led by the University of Southern Denmark noted that the game’s technical and physical evolutions “might raise the risk of muscle injuries”. Sports science has evolved rapidly in recent decades and players are fitter than before, but there are limits to how far human bodies can be pushed.

As of late November, injuries were up 15 per cent on the four-season average, with hamstring issues up by a massive 96 per cent compared to last season.”

On the plus side from a Liverpool perspective, the squad this season is deeper than many realised, with so many excellent young players stepping up. (I said this before the season, but even I’ve been surprised at how well someone like Jarell Quansah has done, as I was thinking more about next season for him.)

But the more of them who are in the XI, the less physicality, experience and pace will be present (as all of those peak at +23). You can carry one or two, especially if the other nine or ten are elite, but once you get to four or five relatively untested youngsters, there will be a noticeable drop in quality.

Conor Bradley is on course to be sensational, but at 20 he’s not as good as Trent Alexander-Arnold, not least because, who is? But also, again, he’s 20, coming back from a back fracture.

However, you’ve seen in the two most recent games the pace he has, the skill he has and the desire and stamina he has. What he lacks is physicality, experience, and the blossoming that saw a similarly-built young Gareth Bale go stratospheric once he got to 23/24.

Owen Beck was looking like he wouldn’t fulfil his potential, but on loan at Dundee he had both Rangers and Celtic interested in Scotland, and is similar to Bradley: slightly built, very fast, very tenacious and great on the ball. He just had to go from boy to man; and right now, he’s back at Liverpool.

Other clubs will have similar youth team graduates, but Liverpool are integrating them this season, just as Arsenal did a few seasons ago in the Europa League and League Cup (and as Chelsea did when they had a transfer ban). Now, some Arsenal fans are questioning why the kids don’t get a chance, even in dead rubbers and cup games. Chelsea are buying other people’s young players and looking to sell their own.

It’s not easy to integrate the kids, as they will not be ‘perfect’. But whenever a club has the time and space to do so, it’s amazing the dividends that can be reaped.

Liverpool have used a dozen young players this season, and it’s reduced the workload for the key men. While none of the younger crop below Trent Alexander-Arnold is established as world-class, Curtis Jones is increasingly outstanding, and for 20, Harvey Elliott is a very mature player who has excelled from the bench, as Klopp continues to use his subs better than anyone else.

But the Reds have probably never had so many talented and fully-integrated youngsters stepping up at once. Jarell Quansah and Bradley are the latest examples.

History

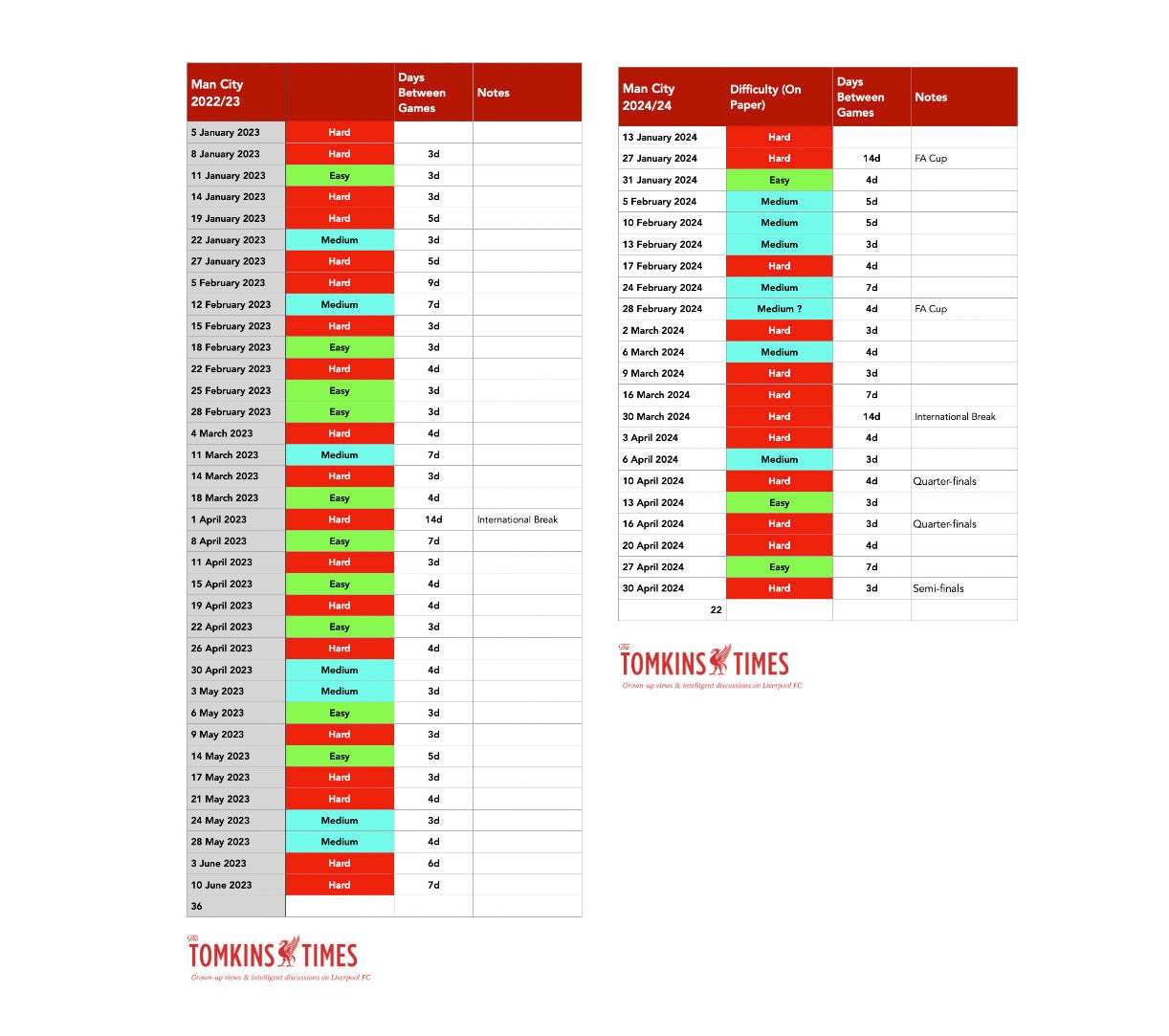

In Manchester City’s run-in last season to complete their treble, their points per game (with all cup games given 0, 1 or 3 throughout this study) rose only fractionally from January 5th onwards against their season ppg: 2.39, from the final 36 games, up from 2.33 across the entire 61 games.

But what's fascinating is that the quality of opposition – which obviously also rose with later stages of cup competitions – made zero difference to City ppg after the turn of the year (albeit they’ve struggled against better sides this year).

What made the huge difference, and what I’ve been studying, is the time between games.

I noticed a while back that both Man City and Arsenal had really tough springs, that could easily break their seasons.

(That said, games can still be cancelled and rearranged at other times, such as due to the FA Cup.)

That’s what really got me focused, as Liverpool’s run-in looked easier, in part due to playing so many tough away games earlier on, and also, having matchweek 20 be Newcastle. Arsenal’s was Fulham.

(Liverpool clearly caught the Geordies at the ideal time. It’s one fewer of this season’s Champions League teams left to face. City just had that luxury too, as Newcastle’s ability to repeatedly cut them open on the break waned as their attackers tired, and there were none on the bench.)

Next, Liverpool’s toughest games are more spaced out in mini clusters, and as I noted in a recent piece, two of the toughest could be like the fifth kicker in a penalty shootout: not required, as they’re part of the final three fixtures.

(But if it does go to the wire, that works against Liverpool.)

Fixture Density and Intensity is my new method of looking at opposition quality plus time between games.

Generally, the better the opposition, the lower your ppg (as is logical), even for a top team.

Also, the less time between games, the lower the ppg.

Combine the two and you have real pinch points.

The longer the run of dense and intense games, the more of a toll you can expect it to take; that’s certainly what I found with Newcastle’s autumn to New Year schedule, although it’s hard to quantify how much tough game after tough games, three days after three days, compounds; especially if injuries beget injuries, then yet more injuries.

Obviously Newcastle are not as good as Man City, Liverpool or Arsenal (although some people tipped them to finish above the Reds again this season), but the relentless nature of tough games meant that by the time they ended up playing Luton and Nottingham Forest, they were cooked.

If you looked at those two games, and also Bournemouth and Everton away in their winter sequence, then you’d have said two or three wins at the very least; instead, they lost all four.

If you replace Luton with Southampton, they played those four clubs eight times in 2022/23, winning six and drawing two; but with an average of a week between matches.

Even with arguably their best outfield 10 against Liverpool, they conceded the highest xG on record (7.2), and were lucky to not concede 10, given how big scorelines are usually higher than the xG. The cumulative fatigue takes its toll.

City are different, but even City rarely go on truly flawless runs, and that includes 2021/22 too.

Indeed, in the run-in last season, City played more elite teams with the luxury of 5+ days rest last season than they played with four or three days rest, yet with four or three days rest they fell below their season ppg, even against generally weaker opposition. (Drawing against Nottingham Forest and Brighton, and losing to Southampton.)

But when they played with five or more days rest they won every single game, bar Spurs away: beating Arsenal, Liverpool, Chelsea, Spurs (home), Everton, Manchester United (cup final), Inter Milan (cup final), Aston Villa, Crystal Palace and Southampton.

In those 11 games, their ppg was 2.73.

But in 16 games with three days’ prep and nine games with four days, the average was 2.25 and 2.22 points per game respectively. That’s the equivalent of an 86-point season, which is good, but not amazing; and that sample was against easier teams than the five-or-more-days samples.

Weirdly, after almost every really tough game they faced a relegation candidate or a lower-league side in the cup: Nottingham Forest, Bristol City, Burnley, Southampton, Leicester City, Sheffield United, Leeds United and Everton.

These directly followed games against Arsenal, RB Leipzig, Liverpool, Bayern Munich, Bayern Munich again and Arsenal again.

As a kind of release valve, they never faced two consecutive games against elite opposition (teams I rated as ‘1’ or ‘2’ – see below) between February 12th and May 14th. They averaged 2.64ppg in this run. They won’t have that luxury this season, as you’ll see later in the piece.

As things stand, and assuming there will be no mugs left in the Champions League, they face nine ‘elite’ teams (in 13 matches) between March 2nd and April 30th. (The FA Cup could add more, or could also see games cancelled and rearranged.)

Opposition Difficulty, 1-10

I rated teams from 1-10 in terms of difficulty. Teams rated as 1 were Champions League quality English clubs, and those European clubs in the top 10 Club Elo rankings; and 2 were Big Six sides who were not in the Champions League, and clubs 11-20 in the club Elo rankings, like RB Leipzig.

Then, 3 was for good Europa League sides, and 4-7 were teams in the various tiers of the Premier League, with 8 the teams who were either relegated (in 2021/22 and 2022/23) or in the relegation zone right now. Anyone below the Premier League was a 10.

Form can change, of course, with Nottingham Forest a 7 when I started the process for this season, but now under a new manager and with some wins already, bumped to a 6; so the current season has a kind of rolling opposition quality rating (previous seasons are set in stone). But the score, even if it changes, is applied for all the teams’ run-ins, so it remains consistent.

To me, City and Arsenal will likely win their round of 16 Champions League games, but then you're looking at likely 1s all the way.

Looking at the Europa League, Aston Villa are the highest Elo-ranked club aside from the Reds, while Xabi Alonso’s Leverkusen are having an amazing season.

AC Milan are ranked just inside the top 20 on the Club Elo Index. So the Reds are likely to face sides of 2 and 3 quality, not 1. Jose Mourinho has spent a lot of money with Roma, and they’re currently 9th in Serie A. (He gets sent off most weeks.) They lost 3-1 at AC Milan this weekend. I wouldn’t want to face his outrageous shithousery yet again, but they’re not a great team. [He has been sacked since I published this part on the ZenDen!]

But another bonus is, come March, April or May, the Europa League can be downplayed if the title is on the line. And Liverpool could potentially still reach the final with a mix-and-match team, or by taking key players off after just 60 minutes (then go all-in on the final after the league season is over).

Data

I looked at the seasons for Liverpool, Man City, Arsenal and Newcastle since the start of 2022/23 and went back to 2021/22 for Liverpool and City, who battled it out for the title and in Liverpool’s case, the quadruple.

(Note: I assigned international breaks “5 days”, for all clubs, as a vague average – in that many players will play just three days before the weekend fixture, and some players won’t play at all. To make it more disruptive, some players won't even be at the club until a day before a match, and instead be on the other side of the world. So it’s a real mess, but for several players there will be two weeks without a game.)

Setting a minimum of six games, I looked at runs that appeared dense in terms of lack of days between matches and/or intense in terms of difficulty; and some were difficult in both areas.

It led to 22 sequences, ranging from six to 16 games (Newcastle’s current winter was included twice, once as the full 16-game stretch, and then the final nine of those matches. The data was collected up to and including their loss at Anfield.).

In total, the runs encompassed 206 games at an average of one every 4.22 days.

I then ranked every run from 1-22 on three categories: shortest average time between games; trickiest opposition; and points-per-game won.

In total, 15 of the 22 runs (roughly three-quarters) saw a lower ppg attained than that team’s season average, and also, the opposition was tougher on average in 14 of the 22 runs than the entire season average.

Half (11) of the 22 runs included both less time than normal and better opponents than across the whole season.

Plus, 11 of those 14 runs with tougher than normal opponents coincided with a worse points per game outcome.

The average points per game during these 194 games was 1.96, against a full season average of 2.14ppg.

Take out Newcastle, the worst team in the study, and it’s an average of 2.1ppg, against a normal average of 2.2ppg.

Of the 64 games included for Man City, they match their season record almost exactly: no better, no worse. However, of the six runs included, two were well above normal, but four fell below. That’s only a third of the time where they really blow the doors off.

But even then, the two runs that yielded really high points per game (2.82 and 2.63) were against teams with a weaker average opposition rating, while the 2.63 run was the only one of the two to include less rest and recovery time; the 2.82ppg run was therefore ‘easier’.

But it's no surprise that City, if given time and if playing weaker team, can go on a big winning run, as they seem to be least likely to lose to really weak sides, in the league and in the cups. They are not flat-track bullies per se, as they don’t just beat the weaker teams, but they are the most reliable in those matches; and this season, less reliable in the bigger games.

And of course, their team and squad costs far more than Liverpool’s and Arsenal’s (and Newcastle’s), so this is to be expected. They’ve had fewer injuries of late, and the return of Kevin de Bruyne will help them, if he stays fit, which isn’t a given with his age and hamstring history. (And they may also be due a proper injury crisis.)

Only one team has faced the triple threat of getting a high ppg when playing the best teams at the shortest intervals, and that is Liverpool in the run-in during 2021/22. That run ranks as more than twice as good as any other run in the study.

It yielded the 5th best ppg rate (2.33), from the 2nd-toughest quality of opposition rating (2.5), with the 3rd-shortest gap between games (3.5 days).

Adding the rankings 5 + 2 + 3 equals 10, with lower the better, obviously.

No one else got combined scores below 25, after which followed 25 again, 26, 28, 30, 31 and 31.

Now, Liverpool were really poor in 2022/23 by their standards, so there’s nothing to speak of there.

And this season (despite going away to many top teams), they’ve had the luxury of no super-tough runs because even a run of tougher league games is diluted by a Europa League game, as Jürgen Klopp mirrored Mikel Arteta last season in not fielding his best team in the competition.

But in the 12 games up to January 1st 2024, the Reds faced Manchester City, Manchester United, West Ham, Arsenal, Newcastle and Arsenal again.

The last two games, while increasing the opposition difficulty, lowered the fixture density (albeit it was still above the season average).

The run ended up averaging a game every 4.0 days, garnering 2.25 ppg, which is a fraction down on 2023/24 so far as a whole (2.37 at this point, after the Fulham cup semi-final), but from relatively harder games in this sequence.

As such, it ranks 10th of the 22 sequences in the study, with category rankings of 8th, 17th and 9th averaging out at a score of 34.

The main point remains: it’s tougher to get closer to 3ppg when either the schedule or the opposition is tough; and the two can perhaps be squared in terms of the toll it will take.

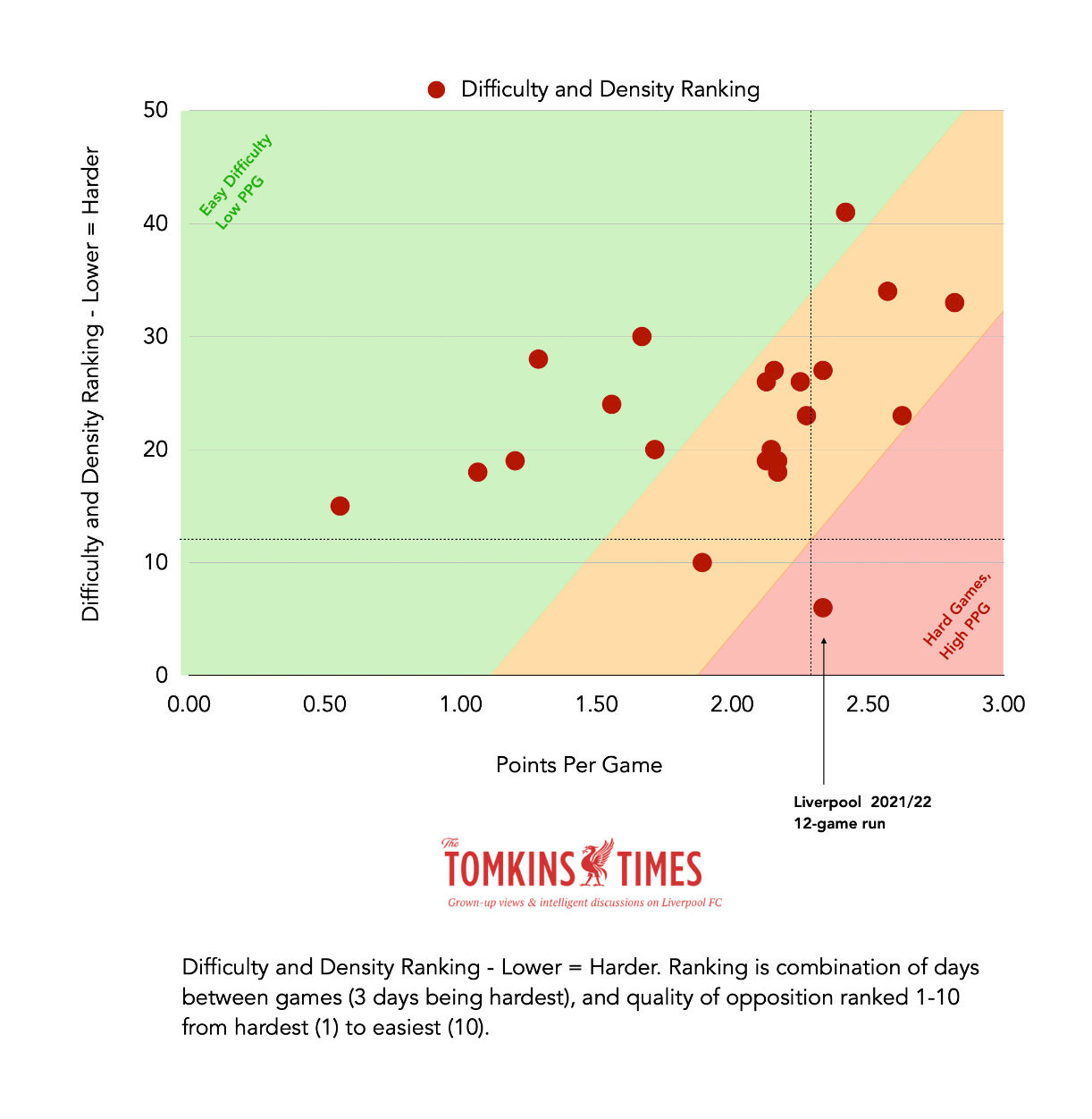

Below is a plot of Density and Intensity vs points per game for the same 22 sequences.

You can see that there is only one sequence in the elite red zone, which is a high points-per-game (2.33) in incredibly difficult games. There are only five higher points per game, and all from much easier schedules.

The closest in difficulty (Density and Intensity) saw Man City gain just 1.89ppg, in nine matches up to May 4th 2022.

Bar the draw at home to Liverpool, three of the four costly results from the nine games were not in the league, however. It did, however, cost them their place in the Champions League and FA Cup finals.

Manchester City 2–2 Liverpool

Atlético Madrid 0–0 Manchester City (CL)

Manchester City 2–3 Liverpool (FA Cup)

Real Madrid 3–1 Manchester City (CL)

Looking only at Manchester City, Liverpool and Arsenal and runs of 10+ games where there was either a tough run of opponents or a dense run of fixtures, the ppg was 2.22 against a season average of 2.23. So, virtually identical.

But obviously that won’t help if chasing a faster pace; 2.22ppg is not ‘winning every game’.

Of course, Liverpool having an easier FA Cup tie in R4 than Man City facing Spurs, and Chelsea facing Aston Villa, means that the Reds are more likely to have a tougher game (and/or just a game at all) in R5 and less time between games if they beat Norwich/Bristol Rovers.

But this is why I think City and Arsenal will face something even more challenging in the Champions League, as both can get past Copenhagen and Porto respectively, albeit Porto are better than the Danes.

It’s almost like save now, pay later.

I would expect the final eight to include City, Arsenal (who could be drawn against each other), Real Madrid, Bayern Munich, Borussia Dortmund and PSG; and then the winners of Inter Milan v Atlético Madrid, and Napoli v Barcelona.

Many of these clubs are in a state of flux, but almost all will qualify as ‘1’ in the scoring system. If the bigger-name clubs win, that will mean huge ties in terms of occasions; even if Napoli or Barcelona are struggling, you’re unlikely to get easy games if they rouse themselves from poor league form, as they have done so far in Europe this season.

Unless there’s a big upset in the round of 16, the quarters and semis will be both tough but also winnable for City, and to a lesser degree, Arsenal. That’s where I think it will impinge on the league form, and again, if they meet each other, that will lead to two big emotional games.

20-Game Run-In Sequences

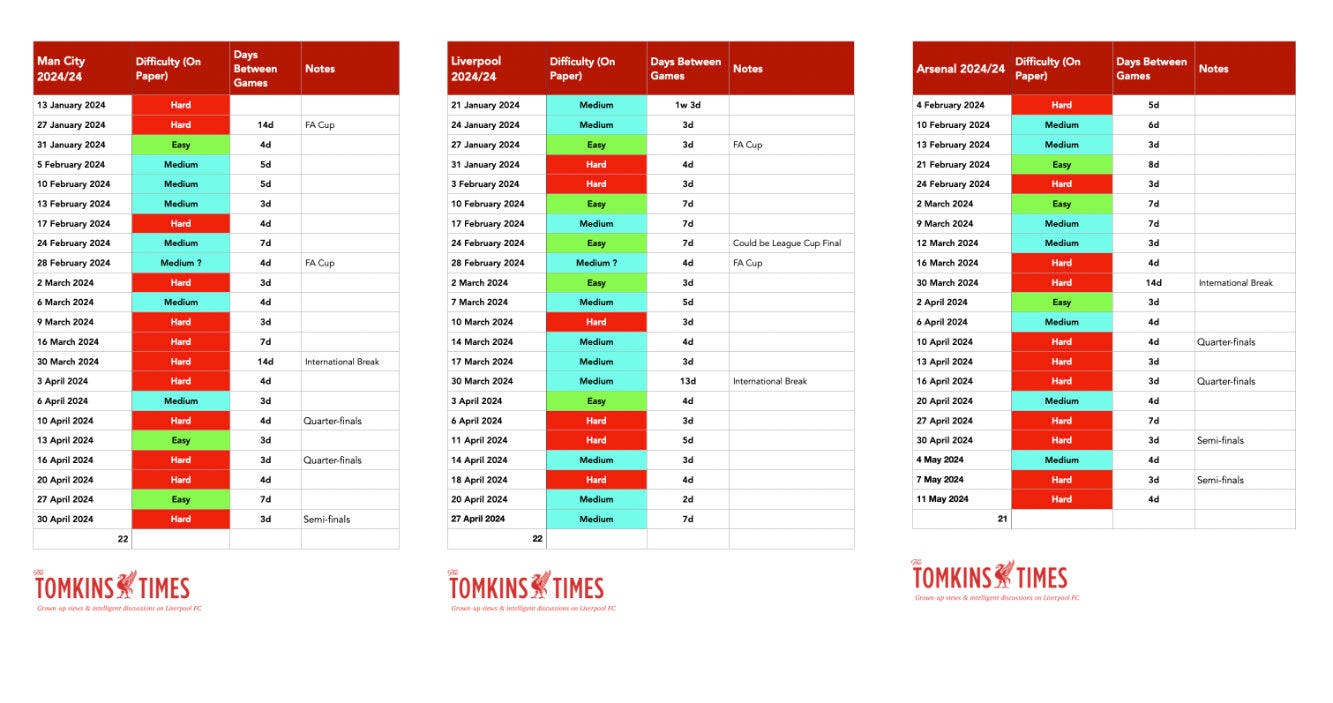

Below is a simplified graphic that breaks down remaining key sequences of 21 or 22 games for Liverpool, Man City and Arsenal, from slightly different starting points, in terms of difficulty (on paper, as you never quite know what you'll face on the day), with opposition again rated 1 or 2 deemed ‘hard’ (in red); teams rated 3-6 as ‘medium’, in blue; and teams rated 7-10, in green, deemed ‘easy’.

(European opponents will be better in the Champions League than Europa League, based on logic, and also the teams left in each competition. Game dates before rearrangements for TV.)

The aim with the garish colour scheme is to get a quick visual sense of the run-ins, albeit home and away hasn’t been factored in. (Again, Spurs, Chelsea and Man City all have to visit Anfield, as do Brighton. Since the graphic was created, Man City beat a depleted Newcastle in injury time.)

What’s interesting is to compare the green cells, and both the sequences and their frequency.

Then, look at Man City last season (compared below, on the left, against this season, on the right). As noted, once past early February they followed almost every tough game with an easy game, to never increase the Intensity, even if the Density was tougher.

These runs are assuming that Arsenal and Man City make it all the way to the Champions League semi-finals, albeit they could go out before then, or meet each other; the same for Liverpool in the Europa League, albeit I haven't projected the FA Cup beyond the next round.

(Despite what Gary Neville says, I haven’t looked at Spurs. After eight and nine games when they were top, I was saying that it was purely down to playing eight easy games, plus a Liverpool team reduced to nine men and shorn of a legitimate goal. If Spurs do go on a run, then I’ll reassess.)

Arsenal’s season from March 16th could be hellishly tough, albeit that would only be so if they progress in Europe.

And Man City from the start of March to the end of April would be similarly tough.

The exact days between all these games is not fully decided yet due to television scheduling, as well as potential FA Cup replays or games cancelled due to either the club or the team they are due to be playing requiring a postponement for the later rounds.

As noted elsewhere, Liverpool’s difficulty rating rises in May, with two very tough games in the final three fixtures. But the title could be won (or lost) by then. My hunch is that City will be ahead of Liverpool by the end of February, but then the tables can turn.

The rest of this article is for paying Main Hub subscribers only. I look at the difference in results between 3, 4, 5 and 5+ days for the main clubs, and how Liverpool differ in a strange way from the overall pattern.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Tomkins Times - Main Hub to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.