Rebuilding Liverpool, Part II: How Young Footballers Reach Peak Strength, Pace and Maturity

Rebuilding Liverpool, In Three Parts - Part Two

Part One - Rebuilding Liverpool: Exhaustion, Fatigue, Resetting and Renewing

Part Two

I’m not a sports scientist, but for this piece have read some research and looked at the clear and obvious data on age vs peak performance in athleticism.

I have also looked at some football data, as to when players peak.

Basically, if you’re judging a young footballer, you’re getting merely a fragment of the picture.

I’m focusing on Liverpool’s younger players as it feels like it is the club policy to integrate more younger prospects.

You cannot just throw them all in together, but transition seasons are when they get blooded, bit by bit. It can be a painful process, but it took time for Jürgen Klopp to build his first great team, and it will take time to build his second one.

The pressing issue, as noted in Part One, is if it totally unravels before then and everything becomes untenable. I don’t expect Klopp to ever be sacked by the owners, but he may walk away if he feels he can no longer get what he wants from the players or the owners. Or, if the club doesn’t get investment but a full sale goes ahead, it may be that new owners do something stupid.

However, only recently, as I keep stating, Klopp was talking about the long-term project. So, I’m basing this on that assumption, until anything changes.

(Note: I’m making this series all free reads, but I try to keep more content paywalled these days, as without subscription income – having been doing this since 2009 – the site won’t survive. Paying subscribers get to be part of the excellent commenting community and access to all content on the TTT Main Hub, and they keep TTT viable.)

Klopp – Long-Term Project

Speaking on the ‘Mike Calvin’s Football People’ podcast, Klopp spoke of the need to rebuild his team:

“It was one of the main reasons why I signed a new contract because I knew it’s necessary. It will not go overnight. I know the majority of the outside world is just interested in the short term but we have to be long-term focused as well, and that’s what we are.”

My hunch is that people don’t appreciate the potential of Liverpool’s younger players, and misunderstand what the ones who are in the team are capable of now, and what they will be capable of further down the line.

While I’ll analyse Liverpool’s young players in Part Three, in Part Two I’ll look at why it can take a couple of years for younger players, and a younger team, to start to really hit the heights.

There are four different areas of physical development I want to focus on: speed, strength, stamina and brain development (which is obviously also ‘mental’).

Speed

To start with, generally, young players are nowhere near as fast as they will become.

Now, on average are always important words. There will be exceptions and outliers. But there are also general truths about what is possible and what is not.

At the age of 17, an elite sprinter will on average be 4.2% slower than at the age of 23. (See table below.)

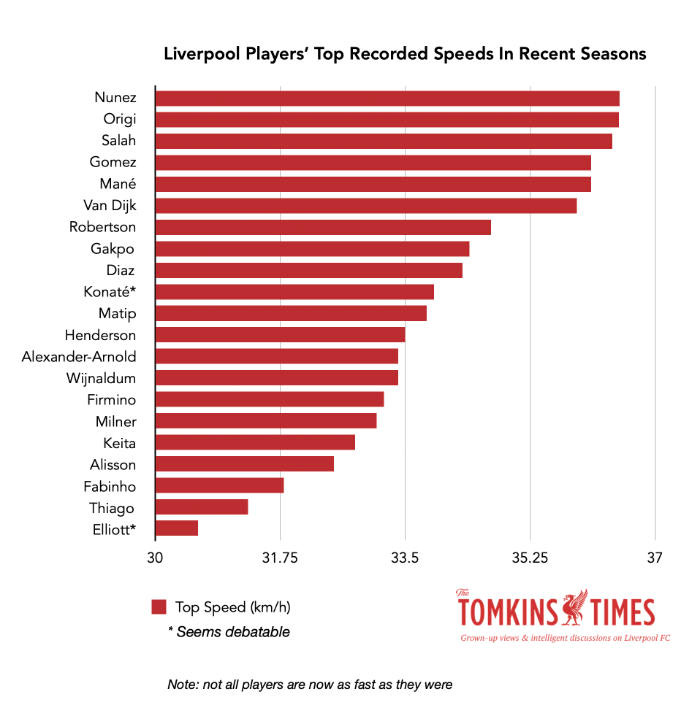

Bear in mind that at elite levels of sport, fractions of a percentage can make a huge difference; and that, in the fastest recorded in-game times of Liverpool’s entire squad (not quite every player was listed in the data I obtained), the range from slowest to fastest is a difference of 19%. Hence why even marginal gains make a difference.

If Darwin Núñez just gets 1% faster, he will be faster than any player recorded in the Premier League this season, being a fraction under that speed right now; a 3% gain will make him the fastest ever recorded.

That said, when players are clocked during a game, it’s the top speed they reach, but ‘pace’ often works in different ways, helped by anticipation and speed off the mark, and there are those who can run harder and faster for longer distances – Núñez and Ibrahima Konaté (and Divock Origi before them) – and those who will quicker into their stride and over shorter distances. Someone like Harvey Elliott may have a lower top speed, but is nippy.

(Similarly, Adama Traoré’s top speed is not that exceptional, but he seems to be able to run at peak speed over long distances, even with defenders hanging off him. He’s no faster than Salah was last season, with identical times, but in the past, Salah was also noted as making 600 sprints per season, which had him about 100 above the next-best in the entire Premier League. It feels like Salah has not only lost a fraction of pace – he’s not even got close to last season’s fastest time – but also that insane ability to sprint repeatedly each game.)

Below is the graph of the top speeds recorded by Liverpool players in recent seasons, which generally makes sense – albeit a couple of their times seem on the slow side to me (the time for Núñez did match the published data I will move onto, so it seems to tally).

Also, these are not necessarily this season. (The ages for the players when hitting these peak times is also not known to me, unless they joined this season.)

The fastest players in the Premier League this season have been aged 22-23, interestingly. (With the exception of Anthony Gordon, who is very close to turning 22.)

While I was writing this piece, an article popped up on Goal, that covered English football’s top speeds in general:

“Mudryk’s figures are just above Anthony Gordon who recorded 36.61 km/h, with Liverpool forward Darwin Núñez and Manchester City star Erling Haaland following with top speeds of 36.53 km/h and 36.22 km/h respectively.

“Fifth on the list is Chelsea midfielder Denis Zakaria who hit a top speed of 36.09 km/h.

“Mudryk’s top speed in the 2022-23 season is comparable to the top speed from 2021/22, which was set at 36.7 km/h by Antonio Rudiger, who was then playing for Chelsea. In the same campaign, Mohamed Salah’s fastest speed was 36.6 km/h, while Adama Traoré also hit the 36.6 km/h mark.

“Manchester City defender Kyle Walker is often considered the fastest player in the Premier League after he hit a top speed of 37.8 km/h in the 2019/20 season…”

So, as well as the aforementioned crop aged 22 and 23, Walker was 28 four years ago when setting that record. Rudiger was 28 last season, Salah was 29, Traoré was 26, as is Zakaria this season.

So the spread of ages from the players named in the piece is 22-29, and the average age is between 25-26, at 25.5.

From other sources, I am told that Arsenal are the quickest team this season – with six super-fast players.

(The average age of their team – if not necessarily the fastest six – is also 25.6, at least two years younger than any of the other Big Six clubs plus Newcastle. Arsenal went through the pain of mediocrity with young players, then emerged all the better for it.)

I struggled to find general athletic data on how fast the fastest sprinters aged 17, 18, 19, 20 and 21 were, to try and plot that specific progression.

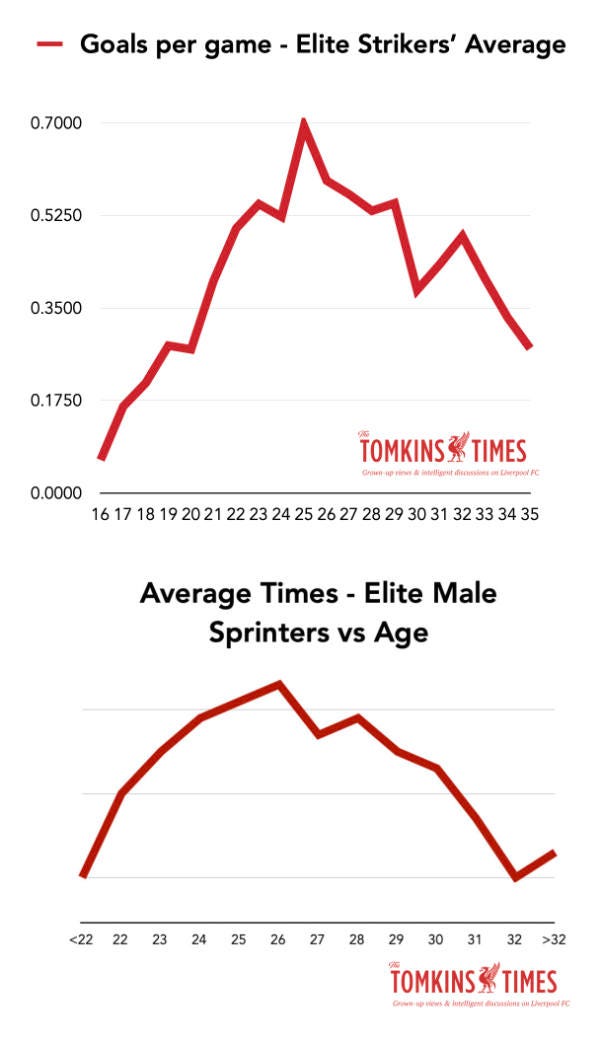

However, although the specific table below, about speed vs age in general, doesn’t divide it into such distinct age groups, virtually all information I could find on peak sprint times says that,

“Between 24 and 26 years though, the relevant mean of annual best records is better than any other three-year period.”;

and that:

“Age of peak performance in world-class sprinters is typically 25–26 years”.

However, by the age of 35, there’s a 16.62% drop-off from the age of 23, and 23 isn’t even the peak age (although 23 was the age that Usain Bolt ran his best-ever time).

The table does at least give the leap from 17 to 20 to 23, while another one, which follows, shows every year from 22 upwards.

“The average elite sprinters will cover the 100m in 10.5 seconds .”

Age – Time

13 – 12.28

15 – 11.65

17 – 11.37 (2.4% faster than aged 15)

20 – 11.10 (2.37% faster than aged 17)

23 – 10.89 (1.89% faster than aged 20)

35 – 12.7 (16.62% slower than aged 23)

40 – 13.4

45 – 14.3

50+ - 15.2

That table is good for showing the improvements still possible by a speedster like Ben Doak, who has only just turned 17.

Jamie Vardy always seemed exceptionally fast well into his 30s, but the sprint data in general seems to suggest that after 29 it’s almost always downhill from there.

Here’s another study, where the drop-off starts at age 28.

Peak Period of a Sprinter – Full Age Range

In another study I found data for the speeds of elite male sprinters aged 22-32, but the graph accompanying the data seemed visually misleading, as the totals were lower when faster (under 10 seconds is a lower figure than over 10 seconds). As such, I’ve inverted the axis, so that the peaks mean peak speeds, instead of troughs on the graph meaning faster.

Improving Sprint Times

Slow players cannot become sprinters, but anyone can do a bit to improve in certain areas, as long as it doesn’t detract from others (i.e. you could add lots of muscle to be a more powerful straight-line runner but it may leave you less agile).

Phil Foden, who is nearly 23 years old now, began working with a sprint coach at the age of 20.

In a Goal interview with the Liverpool fan, Tony Clarke, who coached him to get faster, Clarke explains:

“I told him ‘He could be so much quicker, you know? I explained why, and that was that. I thought no more of it. We carried on with our day.

…

“Foden and Clarke met on a cold evening at Wavertree Athletics Centre, where Clarke sought to correct the imperfections he had spotted.

“It was his first three steps,” he explains. “His stride was too long. He needed to shorten it so that his foot landed underneath his body, underneath his hips.

“If you overstride, you land on your heel. So, essentially your foot stays on the floor for too long. I felt if he could change from a heel-striker into a front-of-the-foot striker, it’d add so much.”

There’s more detail in the piece, but it shows that pace has an envelope – you need fast-twitch muscles to be an Olympic sprinter, but you can work at your speed, as you can your strength and your skill. (You can’t work on your height, unless you resort to Gattaca-esque madness.) Foden was also at an age where he would naturally get stronger and faster.

The same sprint coach said he felt he could make Liverpool’s players faster, and detailed faults he felt he could see in their running styles.

Last Bit on Sprinting

https://statathlon.com/athletics_events_physical_attributes/

“It is quite evident that the vast majority of personal best records were achieved between 23 and 28 years. Between 24 and 26 years though, the relevant mean of annual best records is better than any other three-year period.”

The Older the Stronger

From the same article as the paragraph above:

“Physical strength usually reaches its peak between 25 and 30 years (Shepherd, 1998). Then keeps steady till the age of 40 approximately, when decline starts. This explains why most hammer throw athletes achieved their personal best record at their late 20s – early 30s”

To me, this is interesting as looking at various defenders in their late 20s, so many are big and strong. They can add that peak strength to high levels of experience, whilst still just about at their own personal fastest speed, before that generally starts to dim.

Stamina and Strength

Mixing the stamina and strength from another study:

“168,576 performance times and distances by 2017 athletes in 19 men’s and 19 women’s track-and-field events from 1979 to 2009 were downloaded from tilastopaja.org. Each athlete had finished in the top 16 (track events and combined events) or top 12 (field events) of their event at an Olympic Games or a World Athletics Championships between 2000 and 2009.”

The difference in men’s results were clear, with the relatively young peak for 10,000m runners compared to the late-20s peak of discus throwers.

“…. Age at peak performance for men ranged from 23.9 ± 2.4 y (10,000m mean ±SD) to 28.5 ± 2.2 y (discus throw)”

In other words, 10,000-metre runners peaked at 23.9 give or take 2.4 years, but discus throwers peaked at 28.5, give or take 2.2 years.

In terms of stamina, the really long-distance runners can go on for years, as marathon runners frequently do – but they are all extremely lean; which may be why a lot of more wiry footballers go on longer (Zlatan Ibrahimovic, Ryan Giggs, Teddy Sheringham, Peter Crouch spring to mind), and more hefty, endomorphic body types, like Wayne Rooney, melt earlier; but it’s also hard to play Premier League football if super-lean like Eliud Kipchoge, who won the Olympics in 2021 aged 37:

“Kipchoge [37] successfully defended his title from the Rio Olympics by winning the gold medal in the men’s marathon at the Tokyo Games in a time of 2:08:38, becoming only the third person to successfully defend their gold medal in the men’s marathon… Kipchoge was the oldest Olympic marathon winner since Carlos Lopes won in 1984 at the age of 37.”

(Also, last year, Jo Schoonbroodt, a 71-year-old from Maastricht, ran a marathon in 2hr 54min 19sec, to become the fastest septuagenarian in history. There’s proof that James Milner is not finished yet.)

Goalscoring Peak Age

Goalscoring records are not clearly accurate correlates of peak physical pace and power (see older strikers still scoring goals, perhaps using their canniness to find space and their experience to be relaxed and sure-footed in front of goal), but peak physical power will surely help anyone to hold off defenders, get away from defenders, stay ahead of those defenders, and to make repeated runs without needing to spend ten minutes coughing near the touchline.

(Just as, in all areas of the pitch, peak physical power will surely help anyone to hold off opponents, get away from opponents, stay ahead of those opponents, and to make repeated runs without needing to spend ten minutes coughing near the touchline.)

If you just get faster but not stronger, that will improve you. If you get faster and stronger, you will almost ‘cube’ your improvement.

Greater speed, strength and stamina will multiply it further. You can almost become a totally different player.

Indeed, peak physical power – pace, stamina, strength – will help you resemble two players; any player who can get forward and get ahead of the ball, and then get back with energy and speed to be behind the ball, is essentially able to be in two places almost at once.

This is something Liverpool used to do (constantly the best sprinters/highest intensity sprinters), but in 2022/23, as noted in Part One, has fallen away. Liverpool had a truncated preseason, injuries to peak-age players, and relied on the older members of the squad. A few years ago, Jordan Henderson would be ahead of the ball then back behind the ball; as would Mo Salah. Now … not so much.

In 2015 and 2016 I worked with Robert Radburn on some Tableau data vizzes that looked at the goalscoring records of a whole bunch of strikers across their full careers, and going back to that data, I can find the averages for when strikers are at their most prolific. It’s not about finishing accuracy, but just the sheer weight of goals. It serves as a proxy for performance – just one measure that I could find from my own collated data.

I’ve run the graph below the sprinting graph, as both peak at 25 (but the goalscoring chart starts at age 16; the sprinting at <22). It’s interesting how similar they are.

Peak Age For Footballers by Position

The number of minutes played in the Premier League across 11 years (between 2010-2021) as noted by the Athletic in an excellent piece from November 2021, when compared against ages, shows all outfield positions peak between 25 and 27 (with 28 for a keeper; as an aside, one study I saw a while back showed the peak age for save-percentages for goalkeepers was, on average, 28-30).

As you can see, less than 4% of the minutes played in almost every position by all Premier League clubs over an 11-year period apply to players in all of the age groups up to including 22.

In some positions, their share of minutes rises to 7.5%, but that’s mostly by the ages 23 and 24. The full red shades show the peak age, where most minutes are played, and the averages are clear.

I will take this study and run the current Liverpool squad through the blender in Part Three.

The ‘sprinting positions’ these days – full-backs and wide attackers – peak youngest, at 25, in terms of minutes played. The strength positions – centre-back and target-man centre-forwards – peak later.

Also, the piece notes that 21-year-old wingers attempt 2.5x as many take-ons as 31-year-olds, and 31-year-olds attempt twice as many as 35-year-olds, at just one per game for the oldest players.

This isn’t quite as age-specific in terms of quality, in that an 18-year-olds average over four take-ons per game, but not necessarily in the wisest manner. But it may explain why Mo Salah’s take-on numbers have dropped, albeit the team has been struggling more and he’s been more isolated, and there’s the fatigue issue from last season. Older wingers do slow down, unfortunately.

Learning From Arsenal

In that piece – from almost 18 month ago – Tom Worville also notes:

“Arsenal are a particularly pertinent team to consider because considering all players who’ve played 400 minutes or more in the league this season, Arsenal’s are on average 1.6 years away from reaching their peak, the lowest of any side in the league and almost double that of Aston Villa’s 0.9 years away from their hypothetical peak. At the other end of the scale are Watford, whose most common starters are 3.0 years beyond their peak on average, most likely dragged up by their veteran 38-year-old goalkeeper Ben Foster.”

Arsenal – surprise near-runaway Premier League leaders – provide and interesting contrast, in terms of how much their younger players have developed, to go from fringe, to important, to vital, in the space of two seasons; with the quantum leap taken as of 2022/23, when no one had really predicted such a collective and individual advancement. (Plus, they have the greatest number of super-fast players.)

My analysis has focused on how teams generally continue to perform better when kept together for up to four or five years; but obviously Arsenal’s XI is ageing in, while Liverpool’s age out.

That said, I keep reading about how young Eddie Nketiah is; and he is fairly young. But he’s older than Darwin Núñez, and a couple of weeks younger than Cody Gakpo.

Nketiah was an absolute age-group sensation as a striker up to and including England U21 level – 35 goals in 38 games starting with the U17s, and a stunning 16 in 17 games for the U21s.

Only now, after an improvement last season, is he ‘coming of age’, at nearly 24, after seasons where he scored one or two league goals for the Gunners per season prior to 2021/22 (when aged 22), and also scored three in 17 appearances with Leeds in the 2nd tier when aged 20. He gained experience in the League Cup and Europa League.

But it probably needed an injury to Gabriel Jesus to give him the chance to shine, and have more of his appearances be starts, not from the bench.

There are some even more interesting examples at Arsenal, whose players are worth comparing to the Reds’ emerging ‘Magic Dozen’ at the same stages of their careers. More on that in Part Three.

The Brain

Finally, in this brief foray into some basic science, the final part of the brain to develop is the prefrontal cortex, relating to decision making; it kicks in fully around the mid-20s.

In addition, on average, a man who is 24 years old has the same impulse control of a 10/11-year-old girl, which shows that younger male footballers (like the rest of us) don’t always make the best decisions until our mid-20s; on average, boys are far more physically capable (taller, stronger, faster) than girls at 15, but girls have more self control.

This will effect decision-making off the field, clearly, but also on it – the maturity to make the right choice, and not be too impulsive.

Physicality and Footballers

It seems important to remember what big, powerful, fast players were like when they started out in the Premier League, and were not such big, powerful, fast players.

Still, even players in their late teens just aren’t anywhere near their physical peak.

At that age, it seems harder to build muscle mass given the calories burnt when training, with such fast metabolisms; the metabolic peak is regarded as early 20s.

In addition, the Premier League is full of more elite internationals than 20 years ago, and even 10 years ago, as the English top flight has only in the past few years usurped Spain (and before that, Italy) in terms of allure. Most players now hit the weights in the way they never used to, yet most younger players will be at a disadvantage here; more so than in the past, when everyone was fairly lean.

Look at players from the 1980s when they take off their shirts, and they just had ‘normal’ bodies; while Liverpool’s centre-backs were Phil Thompson (wiry), Alan Hansen (wiry), Mark Lawrenson (wiry) and Gary Gillespie (wiry). They weren’t facing 17-stone strikers, for starters. Liverpool’s strikers were Ian Rush (wiry) and John Aldridge (wiry).

(Of course, Jan Molby was in the midfield…)

Clearly you get very few super-big but also sufficiently energetic 18-year-olds who are also able to be mobile, albeit as I won’t keep stating, these are about averages, and there are outliers.

(But peak performance data is age-specific, even if again, there will be outliers – within reason. No Olympic sprint champion will be 18 or 33. In addition, all data I’m focusing on refers to males, with female patterns slightly different, and with most female athletics world records equaled or bettered by large numbers of 15-year-old schoolboys, which is why Arsenal Women have taken to playing boys that age to improve.)

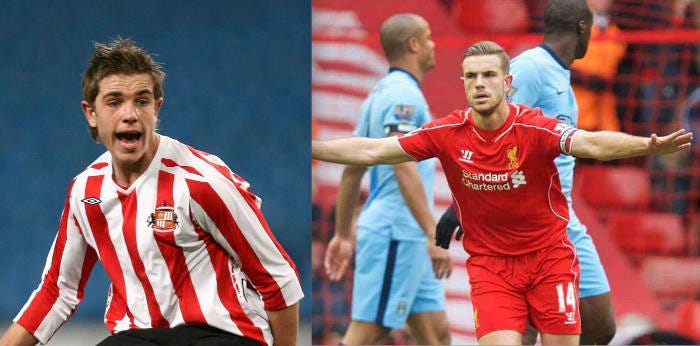

The Jordan Henderson who arrived at Liverpool aged 21 was still fairly skinny. He didn’t have the best of seasons, and played a lot on the right of midfield, which I argued at the time was a good grounding for him, even if it wasn’t his ideal position.

I said at the time that it would help him get up to the expectation levels (the ‘heavy shirt’) at Liverpool, and settle into the team, even if it wasn’t his position to ‘shine’. There were concerns relayed to me by the owners that he wasn’t doing much ‘statistically’ – having been bought as someone who created a lot of chances for Sunderland – and as such they didn’t really understand what he was there for, but I felt he was learning and would become more productive. (And obviously his character is hard to quantify in numbers.)

Whether or not you ever rated Henderson, or you do now in 2023 as he heads towards his decline, the fact is, from 2013-2022 he helped drive several title challenges and also led the Reds to several Champions League finals.

He has, without doubt, been an excellent captain, even if never as good a player as the legend he replaced (who is?). But it was around April 2014, and that 3-2 win against Man City in the first title race of the FSG era, when I first noticed what a ‘bruiser’ he’d become. If you went shoulder to shoulder with the younger Henderson, you’d knock him into the stands. But no longer. Now even Yaya Touré wasn’t going to intimidate him.

Also in 2014, when Iago Aspas and Luis Alberto arrived, Steven Gerrard felt that they had no upper body strength; the bodies of boys, he noted, or something along those lines. Both Spaniards have gone on to have superb careers, but they weren’t physically ready for the Premier League, with Aspas admitting as much, even if he might have fared better arriving a year later, when Daniel Sturridge was injured and Luis Suárez was gone; and only the most talented willowy players can get away with being lightweight. (No one cared if David Silva had huge pecs.)

The only time I’ve heard Jürgen Klopp talking about a player having too much upper body strength is when, four or five years ago, he told Joe Gomez to lay off the weights a bit. Otherwise Klopp talks a lot about the need for younger players to be physically strong enough.

I thought it was worth finding some ‘before’ and ‘after’ photos, of players before they’d filled out, and after they’d filled out.

I’ll also go through some examples of other players whose clear physical development superpowered a big improvement.

First of all, Jordan Henderson, with his early shots at Liverpool looking fairly similar in terms of physique to this one from Sunderland:

Gareth Bale

Gareth Bale remains one of my touchstones for the physical development transforming a player.

He was a skinny teen who, famously, went years playing for Spurs before the side he featured in actually won a game, and was a bit of a joke figure, who almost left Spurs for pittance in 2009, aged 20 (similar to Liverpool, and a young Henderson in 2012).

But then in 2010, aged 21 and after four years in the top flight (and one in the Championship), Bale famously tore Rafa Benítez’s Inter Milan to shreds (“taxi for Maicon”). He scored seven league goals that season, eight goals the next season, and … 23 the season after.

So, Bale suddenly looked the part and went up a couple of levels at 21, then went stratospheric at 23. In terms of league goals scored at the best rate, he peaked at age 26 with Real Madrid (19 in just 23 games), but of course, his body soon started to fail him in terms of recurrent injuries.

Mo Salah

It was noted when Salah returned to English football that he did so with a hefty pair of shoulders, and incredible leg muscles, compared to the player seen at Chelsea.

If you look at the side-by-sides that open this article, try and think which version of the player would be easier to play against … and why.

Trent Alexander-Arnold

Then, Trent Alexander-Arnold, whose best season was 2021/22, compared to the promising but raw rookie of six years ago. (Part Three will look at the stats progressions, year on year, that show how much better he was getting up until this season, which has been tough for a lot of players.)

I still don’t think he uses his improved body and height of around 6ft very well at all defensively, but at 24 he’s not going to be at his defensive-minded peak.

These are just a few examples, but there are many more.

Remember, talented players who develop physically can really become game-changers – the issue is if they don’t develop physically (or get injured, or become lazy or disenchanted).

But physical players with no talent have their limitations from the start, and while anyone can improve with practice, they probably won’t get good enough.

Equally, super-strong players in U18 football may have less scope to physically develop later, and it may be that they look amazing against kids but are cancelled out by powerful physiques of the Premier League, and don’t have a lot extra to add.

Ugly Duckling Phases and Growing Pains

One weird thing with player development is a strange or sudden growth spurt or a debilitating growth-related condition that slows their ascent or even changes their entire game. It can obviously happen at any point in a player’s development throughout their teens, maybe even into their early 20s.

Cody Gakpo, for example, grew 20cms in no time at all, and, “There were times in the academy when he had difficulties with his height and feet size”, a Telegraph article states. U23s centre-back Billy Koumetio, 20, was a little winger; now he’s a 6’5” centre-back.

With Man United’s Scott McTominay, there “were doubts that he would ever make it as a professional, being 5ft 6in when he was 18 before an incredible growth spurt to 6ft 4in by the end of 2015”.

Back at Liverpool, Virgil van Dijk told Sky Sports a couple of years ago:

“I played in the academy of Willem II for 10 years. There was a period at Willem II when I was around 16 that I was on the verge of not going through to the next year of the academy. I was not good enough at all, I was on the bench a lot. In the summer I had a growth spurt and after that everything went really well. I had an injury in my groin because I was growing so much, but after that I made big steps.”

(Incidentally, both Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen both were talented but not entirely remarkable basketball players until they had crazy summer growth spurts, to eventually end up together in the greatest team ever, or so the famous Netflix series tells me. Without doubt their talent magnified when they went supersized; and Jordan, like others, spoke of the fast improvement once he started hitting the gym and began to get bigger and stronger into his 20s.)

Even then, van Dijk didn’t end up in a Big Five European league until 24, and at an elite club until 26. He didn’t play for the Netherlands until he was 24.

For Stefan Bajcetic, the sudden growth spurt came a few years ago, in his early teens. It’s a reminder of how things like balance can be knocked out of whack, and how a new centre of gravity takes some getting used to. His old youth coach told the Liverpool Echo:

“As the 2004 cohort transitioned into a more well-structured regime from under-12s onwards and competed in renowned competitions such as the La Liga Promises, a string of growth spurts during his early teens would briefly hinder Bajcetic’s progress as he became, what Otero can only describe as, ‘uncoordinated’ with his flailing limbs.

“There were a few moments when Stefan was very uncoordinated with his body because he grew so quickly and a lot of people had things to say [criticism], but after that he was very, very good,” says Otero.

Bajcetic still needs to fill out. He will get stronger, gain more stamina, and probably get faster. He’s fading later in games, because again, he only recently turned 18. He’s brave and strong for his age and size, but he’s half the player he will become.

I also remember Curtis Jones as a dazzling wiry winger in the U18s under Steven Gerrard, then seeing him playing up front in a youth game (maybe the U23s) a year or so later and wondering who the hell the big, lumpy striker was. He looked nothing like the same graceful, free-flowing player. Over time he grew a bit leaner, and started to look like a dribbler again.

Even so, he’s just had a bad year with injuries, but even having just turned 22, is not at his peak yet. It’s not not quite clear what kind of player he is, but even at 22, there could still be a quantum leap by the time he’s 24, while for the role of an attacking midfielder, the peak years start at 26.

As for Gerrard, Jones’ old U18s coach, Wikipedia states

“…he began to suffer from persistent back problems, which sports consultant Hans-Wilhelm Müller-Wohlfahrt later diagnosed as a result of accelerated growth, coupled with excessive playing, during his teenage years. He was then beset by groin injuries that required four separate operations.”

I remember those issues well, and it took a while, into his 20s, to get over the constant injury problems. As I keep noting, it took him 50 games to score more than one goal for Liverpool, then almost 200 followed after that.

Both Kaide Gordon and Calvin Ramsay have had issues with growing this season. Fingers crossed their issues are behind them, but it may affect different younger players next season.

Young Players: Tested On Loan

When young players go on loan, the aim is to gain experience, ideally at a club that will play them regularly, if they merit it. The intensity and pressure will be far greater than any U21 match – against fully grown men, perhaps in front of 20,000 fans or more.

Unless a player is over 22, a loan is usually developmental; after that, it may be to get him ready for a move, or off the books. The general rule, however, is that goalkeeper and centre-backs peak latest. A centre-back being on loan at 22 is different from a winger; and the level of the loan is indicative of where that player is right now.

How Good Is the Championship?

When talking about how well Harvey Elliott did at Blackburn, and how well Tyler Morton is doing now, I pondered how, as the Premier League gets stronger and stronger (and richer and richer), the talent will drain down the English system (especially as clubs in the 2nd tier spend crazily; probably more than elite European leagues).

One thing I wanted to question was whether the Championship is a stronger league than Brazil’s Série A? It seemed unthinkable … until I thought it.

The latter will presumably be better technically, but all the best Brazilians are usually long-gone by 19. (Plenty seem to be … in the the Championship!)

I thought of it when watching this video of Tyler Morton, and how, if it had been of a South American kid who was 19 at the time in Brazil’s Série A, if I’d think “wow, that’s a potential superstar”. And I think I would. I keep sharing this video with that thought in mind, and also because it shows me a player developing at an exciting rate.

There are lots of ex-Premier League players in the 2nd tier in England, and lots of clubs who have plenty of full internationals. Several of these are on loan from Premier League clubs, which means that a fairly prolific Turkish international striker such as Halil Dervişoğlu currently plays in the Championship; when 15-20 years ago the same standard of player would be starting in the Premier League, at a club like Bolton or Stoke.

Players like Ismaïla Sarr and Sander Berge are far too good to be plying their trade at that level, but they are big buys contracted to clubs who got relegated.

I checked three of the teams battling for promotion, albeit two were recently relegated (one a bit longer ago), to see the profile of player in that division.

Burnley currently have eleven full internationals, and various other U21 players from strong nations.

Jóhann Berg Guðmundsson, 82 caps (Iceland).

Jay Rodriguez, 1 cap (England)

Vitinho (Brazil U20 caps)

Darko Churlinov, 18 caps (North Macedonia)

Manuel Benson (Belgium U21 caps)

Connor Roberts, 44 caps (Wales)

Jack Cork, 1 cap (England, but 39 England age-group caps)

Taylor Harwood-Bellis (England U21 international on loan from Man City)

Bailey Peacock-Farrell, 35 caps (Northern Ireland)

Anass Zaroury, 2 caps (Morocco, plus U21s for Belgium)

Josh Cullen, 22 caps (Republic of Ireland)

Samuel Bastien, 8 caps (DR Congo)

Ian Maatsen (Chelsea player, Holland U21 international, on loan)

Halil Dervişoğlu, 15 caps (Turkey, on loan from Brentford)

Jordan Beyer (Germany U21 international on loan)

Arijanet Muric, 28 caps (Kosovo)

Then look at Sheffield United, relegated some time ago, who have more – twelve full internationals, and various U21 stars.

Adam Davies, 4 caps (Wales)

George Baldock, 6 caps (Greece)

Enda Stevens, 25 caps (Republic of Ireland)

John Egan, 30 caps (Republic of Ireland)

Max Lowe (6 England U20 caps)

Anel Ahmedhodžić, 18 caps (Bosnia and Herzegovina, plus one for Sweden!)

Jack Robinson (ex-Red, 10 England U21 caps)

Ciaran Clark, 36 caps (Republic of Ireland)

Rhys Norrington-Davies, 13 caps (Wales)

John Fleck, 5 caps (Scotland)

Sander Berge, 32 caps (Norway)

Oliver Norwood, 57 caps (Northern Ireland)

James McAtee (Man City player on loan, England U21)

Rhian Brewster (18 England U21 caps)

Oli McBurnie, 16 caps (Scotland)

Iliman Ndiaye, 5 caps (Senegal)

Daniel Jebbison (current England U20 international)

Watford, meanwhile, have TWENTY full internationals on their books, and yet they have a measly 40% win-rate this season.

Iliman Ndiaye, 5 caps (Senegal)

Maduka Okoye, 16 caps (Nigeria)

Daniel Bachmann, 13 caps (Austria)

Mario Gaspar, 3 caps (Spain)

João Ferreira (lots of Portugal youth caps)

Hassane Kamara, 7 caps (Ivory Coast)

Craig Cathcart, 69 caps (Northern Ireland)

Ryan Porteous, 1 cap (Scotland)

Christian Kabasele, 2 caps (Belgium)

Kortney Hause (10 England U21 caps)

Francisco Sierralta, 15 caps (Chile)

Imran Louza, 11 caps (Morocco)

Tom Cleverley, 13 caps (England)

Ismaël Koné, 9 caps (Canada)

Ken Sema, 14 caps (Sweden)

Dan Gosling (England U21 caps)

Yáser Asprilla, 2 caps (Colombia)

Leandro Bacuna, 44 caps (Curaçao, after 10 Holland U21 games)

Edo Kayembe, 10 caps (DR Congo)

Keinan Davis (England U20 caps)

Rey Manaj, 31 caps (Albania)

Henrique Araújo (Portugal U21 caps)

Ismaïla Sarr, 52 caps (Senegal)

Samuel Kalu, 16 caps (Nigeria)

Britt Assombalonga, 8 caps (DC Congo)

Matheus Martins (Brazil U20 caps)

Not all of these are current or elite internationals, but they feel like they’d have been Premier League players 10-20 years ago. Several are good enough to be in the top flight now.

So when a player does well on loan in the Championship, it’s got to be a good sign.

It doesn’t mean he’ll make the grade at Liverpool, but the 2nd tier is a strange league, full of internationals and also the brutal physical style and the 46 league matches, before four teams enter the playoffs.

It’s one reason why I now have higher hopes for Tyler Morton, who not only looks great in clips, but has won rave reviews for his full performances. He’ll turn 21 next season, and will likely be a bit bigger, stronger and faster, too, as well as wiser from his year in the tier two.

Players Who Were ‘Not Good Enough’

At ages 19-21 – maybe ‘not good enough’ – for the Premier League, definitely (people would have said) for Liverpool

Andy Robertson

Sadio Mané

Mo Salah

Virgil van Dijk

Alisson

Fabinho

Darwin Núñez

Luis Díaz

Diogo Jota

Roberto Firmino

Ibrahima Konaté

Naby Keïta

Cody Gakpo

All of these players had achieved relatively little by the age of 21 (compared to their later achievements), even if they showed potential. Some were playing at a good standard, others were not. None was a clear superstar at 19, 20 or 21. None was anything like what he would become in his peak years.

From other clubs, players who were not first-team regulars or clear stars aged between 19-21, or who ‘flopped’ or underwhelmed for some time in the Premier League when aged 21 or older, but who have become top/coveted players:

Kaoru Mitoma (25 now, first pro game aged 22!)

Moises Caicedo (big strides the past year)

Enzo Fernández (ditto)

Reece James

Mason Mount

Harry Kane (several unremarkable loans)

Son Heung-min

Anthony Gordon (came good around age 20)

Dominic Calvert-Lewin

Casemiro (slow start at Real Madrid 10 years ago)

Harry Maguire (he looked good at Leicester in his mid-20s)

Solly March (looks good now, aged 28)

Riyad Mahrez (2nd tier France until near mid-20s)

N’golo Kanté (2nd tier France until near mid-20s)

Kevin De Bruyne (Chelsea ‘flop’ early 20s)

Rodri (Villarreal bit-part player at 20)

Ederson (Benfica B team aged 21)

Manuel Akanji (Dortmund regular only once aged 22)

Kyle Walker (first full Premier League season aged 21)

Miguel Almiron (joke figure until recently)

Joelinton

İlkay Gündoğan

Aleksandar Mitrović

Martin Ødegaard (teenage sensation who ‘vanished’ for a while)

Eddie Nketiah (older than Darwin Núñez!)

Granit Xhaka

Arnaut Danjuma

Jamie Vardy

Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang (un-prolific until 22)

Kieran Trippier

Dan Burn (not a Premier League regular until aged 26/27)

Pierre-Emile Højbjerg (Bayern debut at 17, but sold by 21)

Most will be self-explanatory as to the difficulties they faced, or their late-blooming/improving status, if I haven’t added a brief thought in parentheses.

Plus, Marcus Rashford – the best season of his career so far, aged 25, after the worst, aged 24. Was a teenage sensation, but never got into double figures for league goals until aged 21. An example of improved environment after personal malaise as he hits his peak years. Currently has his best goals-per-game record for both Man United and England.

And obviously there will be many, many more – I mostly scanned the player lists of the bigger clubs, but smaller clubs will have similar stories (such as Ivan Toney, a Peterborough player until the age of 23 after Newcastle let him go).

They’re just a selection of players whose games rapidly developed or solidified; some, like Xhaka, March, Almiron and Gündoğan, doing so aged 28 or over.

Mitrović, also 28 now, has got stronger and stronger, and more and more street smart – age can bring a wily aggression – having been a 6’2” and well-built young striker who maxed out at around 10 goals every good Premier League season, but who now has 11 in 18, after having also become more prolific in the Championship last season, as someone who has yo-yoed between the divisions. (He got 4 in 25 in his first Championship season in 2016/17; then 12 in 17; then 26 in 40; then last season, the incredible 43 in 44.)

Environment

For me, it’s about the players finding the right environment, where they are improved by coaching and training, and where they feel settled and relaxed, but also motivated and fired-up. Then, they can develop physically: strength, pace, stamina; and become wiser, smarter.

(As covered in Part One, obviously exhaustion can play a detrimental role at times, and make players look worse.)

But it also needs them to be used in the right way, by the right manager, at the right club, supported by the right teammates. (And to have the right fortune: Harry Kane badly scuffed his shot to break Jimmy Greaves’ record, whereas Darwin Núñez, at Wolves, hit an excellent low drive from a wider angle that the keeper somehow saved with his foot – just one example of the role luck can play in any given moment. And there’s no law to even luck out – you will get good luck and bad luck but no one measures it out equally; and you can also get Paul Tierney as a ref most weeks, and that’s just plain unfair.)

I’ve said for years that, to paraphrase Heraclitus, just as no man ever crosses the same river twice (because it’s not the same water flowing by and he’s not the exact same man), no player is ever the same in two different environments.

But if you get a special group of players together and stick with them, then research has shown that they will likely improve as a team up to and including the fourth year.

Now, the ‘teams’ studied are never quite the same in football, as it’s a squad game and it’s rarely the same XI every week – in contrast to a team of surgeons, airline pilots or basketball players studied, with smaller numbers of team members – but the shared knowledge, trust, understanding and rehearsed, instinctive movements are vital.

Liverpool fell down in 2020/21 in part as there were ten debutants in the major competitions due to all the injuries, including a few new additions who needed to settle in.

(The two new defenders brought in, who had much more experience of senior football, fared worse than the two as-then mediocre rookies, Nat Phillips and Rhys Williams, as the latter pair were part of the squad already … and also, bloody tall.)

This year the figure could get close to that, but with every game and even every training session, knowledge is being built and shared.

Already, Gakpo, Núñez, Carvalho, Bajcetic, Arthur Melo, Doak, Ramsay and Clark have all made their Liverpool debuts in the league or the Champions League (or both). That’s eight, in just over half a season, and even the two Academy youngsters only joined the club a short while before this season.

The science of teamwork suggests that Klopp and Lijnders know what to do: smaller groups where there’s more unity and not too much churn (in contrast to Chelsea and Forest creating bloated squads where there will be too many to even train properly, and unhappy pros on the sidelines snarking and leaking – it might work, but there’s a big risk of an infectious dissatisfaction spreading).

Pep Guardiola knows this too, and he also knows that a brilliant but unhappy player is better off unloaded (to Bayern, in this case) than staying around to undermine his authority and the team bond. Having already off-loaded Raheem Sterling (who has now been made peripheral at Chelsea), Guardiola is giving young Rico Lewis, 18, a run. It feels like City are also in a bit of a transition (Kyle Walker is nearly 33, Kevin de Bruyne was benched yesterday), with Erling Haaland scoring goals in a team that, overall, seems less dominant and wins fewer points. And this is a City team with just two injuries right now, compared to the six Liverpool were missing at the weekend (plus Fabinho).

But the biggest steps for Liverpool, aside from those new players finding their feet (just as it took Andy Robertson, Fabinho, Firmino, Konaté and others time), will be from the best young players who grow stronger, faster, fitter and wiser.

Because so many of them, right now, are ahead of where so many of the best Premier League players were at the same age.

And at that age, that’s the most you can ask for. They may need loans, or they may just get the usual blooding of a few minutes in their first season, a few games in their second, a few starts in their third, and be up and running by their fourth. Some will bypass that, and get their quicker. Some will go by the wayside, due to injury.

You can’t guarantee that they’ll become the next Bale or Gerrard, or even Henderson, but if they’re comparable at the same age – and are given elite coaching in an elite environment – they have the potential to get close.

Part Three will look at these younger players in depth.

Commenting is for paying subscribers only.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Tomkins Times - Main Hub to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.