Sense Not sentimentality - Alonso the Perfect Fit, But Who Else Is There?

✅ Free Mega-Post: deep dive into more reasons to back Alonso, and what the alternatives offer

Xabi Alonso?

Rúben Amorim?

Roberto De Zerbi?

Andoni Iraola?

Thomas Frank?

Roy Hodgson?

Sense Not sentimentality - Alonso the Perfect Fit, But Who Else Is There?

I’m still dealing with the shock of Jürgen Klopp leaving this summer by thinking ahead, to not get into catastrophising as if it’s a cliff-face we’re heading towards; to see the promise on the horizon, like light ahead of the dark clouds of late May 2024.

(Albeit saying goodbye to Klopp is also something to paradoxically look forward to and savour: to give a proper farewell. To celebrate what has been, and I will enjoy the rest of the season, whatever happens.)

As well as who should be the manager, there’s the big issue of how.

And how soon.

So, this is a long piece: 12,000 words or so.

But it’s in sections, and as well as a free read (albeit it may later be paywalled, and comments are always for paying subscribers only), it comes with free caffeine patches coded into the letters ‘p’ and ‘z’.

(Scratch and sniff your screens to release chemicals.)

The full version of this article may not appear in the email newsletter version due the tactical/data images imbedded.

Four Favourites Via Bookies

Xabi Alonso – 1/1

Ruben Amorim – 7/1

Roberto De Zerbi – 8/1

Pep Lijnders – 10/1

Pressing

For all the talk of pressing on the pitch, Liverpool need to prearrange Jürgen Klopp’s replacement ASAP – ideally this month – for various reasons.

I’ll go over the candidates in this piece, and why I’m still keenest on Xabi Alonso (with additional analysis from Mizgan Masani who writes TTT’s tactical Substack).

I wanted to further my case for Alonso as the replacement for Klopp, but also look at the records and playing styles of the other names mentioned.

I’ll revisit some points I’ve made before, only in more depth, and also look at some new angles.

But there is so much to sort out. First, when and how.

Three keys players will be down to their final year in the summer, and two super-gifted older pros who may be worth keeping (on reduced wages) are free agents this summer.

I doubt anyone wants to leave Liverpool, but right now there’s no easy way to make decisions; not least as the players may also want to know who the manager will be if they are to commit long term, and crucially, if they are in his plans.

Which players the new manager wants to keep and build around is vital, albeit you’d expect it to include Trent Alexander-Arnold, Virgil van Dijk and Mo Salah. That said, the latter two are nearing the melt-zone; in the final imperious peak period of their careers, logically. (And Alexander-Arnold will surely sign a new deal.)

You probably wouldn’t want to try and start building without them, albeit Salah leaving to Saudi for silly money would help sign top replacements. But that seems less likely, given the dullness and low quality of that league.

(I don’t think this squad needs a lot as things stand, but an unstoppably fast winger is something it lacks. In time Ben Doak could be that player, but at just 18, not for a while. Mo Salah has slowed by a few percent, and none of Diogo Jota, Cody Gakpo and Luis Díaz are close to the fastest players in the Premier League, which leaves Darwin Núñez as the only super-quick striker. Dominik Szoboszlai is just as quick, playing from midfield, but is a winger for his country. Conor Bradley, originally a winger, could also play in midfield and up front again, in time. He’ll also get faster, as no one is at their fastest at 20, unless injury stops them getting faster before the peak of mid-20s for pace.)

However, what a new manager wouldn’t want is a first season with key players able to negotiate leaving for free less than six months after he arrives, and sense of uncertainty and unrest.

Director of Football, new manager, new contracts and new signings (as well as who to release and sell) are all part of a potential catch-22 loop; a chain reaction, but how do you get the reaction started?

A DoF may choose the manager (they normally would, albeit Liverpool didn’t have a DoF in 2015, with Michael Edwards only later taking up that role), but a DoF could take ages to appoint, and wouldn’t necessarily understand the needs and culture of the club right away, nor the squad’s strengths and weaknesses, if not someone from within.

Will Spearman is said to be leading the search, as Dr Ian Graham did in 2015. But it will surely involve other people, too.

A new manager would ideally have as much of a preexisting link to the club as possible if the DoF is totally new to the club, in order to settle in more quickly.

While back to front, in this case it also makes sense to appoint an elite manager and then find a DoF to suit his approach, as long as the approach fits in with the way the club does things (modern football, data for scouting but also traditional scouting, and the way contracts, bonuses and incentives have been used).

Let’s face it, Liverpool aren’t going to approach Chris Wilder, are they?

Obviously a new DoF could not be sorted while Klopp was the ‘eternal’ manager, and Jörg Schmadtke was installed as ‘his’ man.

While the summer had some very strange moments (the weird, prolonged bidding for Romeo Lavia, and the sudden explosive offer for Moises Caicedo), we saw the benefit of the Klopp/Schmadtke partnership in getting Alexis Mac Allister (albeit Julian Ward led that as his final deal), and more so, Szoboszlai, Wataru Endo and Ryan Gravenberch from German football.

You’d say that was all money well spent, with Gravenberch probably needing another six months and a proper preseason to find his best form (he has all the ability in the world, and needs time to adjust).

The relationship between manager and DoF is vital, as is the relationship between DoF and the hierarchy.

Were Pep Lijnders to have been considered to replace Klopp, he would have represented continuity, but also virtually no managerial experience; and from what I heard over the years, seems to have burnt some bridges behind the scenes.

As I’ve said before that, going back to 2019 and 2020, it felt like he was being groomed for the job, but that was before there were issues between the football side of things and the transfer side of things.

I also think that if Lijnders was in line for the job it wouldn’t have been announced that he was leaving at the end of the season. After all, if Klopp was handing over to him, that is something that could have waited to the summer, as the continuity would be in place.

But Klopp did the right thing to give the club time. And once it was announced, it made sense to be clear about who is following him.

(There’s always a chance that Lijnders may still be considered, I suppose, and that the process was started with a blank slate. Also, to have said that all Klopp’s other staff were leaving in the summer, but not Lijnders, would look like he had the job; as his next job, he understandably always said, will be as a manager. I think he’ll get a good managerial position, given his qualities, but not one as big as Liverpool, even if he has been a key figure in shaping the tactics of the club. And of course, if Liverpool really wanted to make him manager, they wouldn’t have opened up the chance for Lijnders to negotiate with other clubs by saying that he’ll be free in the summer. I still think, if the job was to be his, he’d have been given it already.)

As such, Mike Gordon, Billy Hogan and Will Spearman are the continuity. Mike Gordon being more hands-on again is important.

I’ve seen some managers linked with the job say they’ll make a decision on their futures at the end of their ongoing seasons, and I understand their focus on that.

But that’s too late for Liverpool.

You can’t wait until close to June, then start negotiations. Negotiations can take time, and as the process progresses, people can drop out or be found unsuitable, and then it’s back to square one, except in July, not June. There isn’t time.

Players futures need sorting well before then.

To only discuss the job and appoint in the summer means the new man has to assesses his squad in preseason. Again, that’s too late. A sense of uncertainty about Klopp’s replacement is not an issue right now, in early February, but in time it will be.

None of that need be a catastrophe – the club won’t fall apart if the decision is delayed – but it seems far from ideal in terms of making next season a success.

Some transition will be required – as I will show via Mizgan’s analysis, none of the main candidates, as well as not being a larger-than-life charismatic German, will play the exact same brand of football.

I mean, who else plays exactly the same as Klopp’s Liverpool? No one.

But change needs to be kept as minimal as possible, to not lose the excellent potential and development of Liverpool 2.0.

Granted, it’s better to wait to June to appoint the ideal manager than to rush into appointing an inferior option now, but just as players sign pre-agreements and then focus on the rest of their season with their current club, Liverpool surely have to approach it that way with a manager.

Even with a vacancy at Barcelona in the summer and possibly Chelsea too (and Man United?), Liverpool is the best job in world football right now, as you have a young squad currently challenging for every trophy, and an ownership that backs managers. Unlike Barca and Chelsea, it’s a club that doesn’t have a ton of debt and terrifying long-term financial commitments to drain future resources, and whether or not Liverpool win the title, they should at the very least be in next season’s Champions League.

However, getting into a battle over certain managers with Manchester United – if they part ways with Erik ten Hag (due to the new ownership situation wanting to change direction) – could be challenging; unless the man in question is a Liverpool legend. United are still a massive draw, but not as well run as a club, with nearly £400m owed on players they’ve already bought, and unlikely to be in the Champions League next season unless it goes to 5th place in England.

And of course, Barcelona is a mega-club – arguably the most romantic in the world – and managers and players tend to ignore that it’s a total basket case, full of lunatics pulling levers behind the curtains like it’s Oz.

The Reds also surely want a manager who can settle on Merseyside, relate to Liverpool FC, and relate to the city. Klopp’s humble German background and outlook on life made him perfect for the job; he had the right ‘attitude’.

And with almost certainly no continuity via the existing coaching backroom staff, knowledge of the club, the city, the pressures, becomes more important.

The only elite manager who guarantees that is Alonso, whose children were born in the city, and who love the club, like he does.

(As he said six years ago, he’d love to do the job one day; and it’s weird to hear Steven Gerrard mentioned as the one who’ll do the job first, after Gerrard’s career came off the rails to a reasonable degree, after a promising start.)

The north of England is not as sunny as Spain or Portugal, and you have to accept the cold and dark winters; training in the snow at times, and certainly the wind and the rain.

For anyone who has never played, managed or lived outside of far warmer climes, I’d be slightly more wary. It’s not a dealbreaker, as people adjust; but just another factor in feeling that the “fit” is right. Even Klopp has said you have to train differently in the cold to the warm.

Also, as with Klopp, ideally the club want someone who really wants the job. Who isn’t going to be tempted by something else.

And for Alonso, his greatest affinity seems to be with Liverpool, not Real Madrid or Bayern Munich. (Obviously Sociedad is his first love, but they’re not a big enough club and he did three years with their B team in the Spanish league pyramid.)

As I’ve said before, a club like Liverpool can go more left-field in times of crisis, when everything’s already a mess. What’s another year of mess? After a mess, the next guy normally has a year of leeway, to make the transition.

But you don’t want to get a golden handover wrong.

A bad appointment wouldn’t break “everything” (most of the best younger players will still be around). And clubs recover from bad seasons. But there’s too much potential to risk wasting it on too much of a gamble.

And again, the entire process loop of “manager/DoF/new contracts/new players/selling or releasing players”, needs to start moving soon.

There’s a chance that uncertainly may creep in with some players; a risk of drift, especially if the season peters out (albeit I pointed out on my separate ZenDen Substack how the run-in favours the Reds).

And one thing Klopp has ceded is power to any player who wants to down tools and outlast him.

I don’t think there’s anyone in the squad to consciously do so, as they’re all so professional and (as I like to keep it here at TTT) it’s a dickhead-free zone; but subconsciously anyone dropped or omitted or increasingly on the fringes – as would be the case for a few if/when everyone is fit – may know he’s not fighting for his future with this particular manager. (On the other hand, everyone now has to start potentially impressing his replacement.)

Klopp has also created a situation that could go either way: inspire or overwhelm.

The same applies to the added pressure of the new documentary, which brings greater scrutiny, if thankfully no changing room access, the sanctity of which must be protected at all costs. Everything has been ramped up. It’ll be even more emotional, for good or bad.

But Klopp definitely did the right thing to give the club advanced warning, once he felt he was running out of energy, as leaving it to the summer would have made things far more complicated.

However, as it stands, it’s still pretty complicated.

Would Alonso Take the Job?

For this, I’ll quote from a BBC article. Even though Alonso clearly wants to manage Liverpool one day, the only question would be one of timing. (That said, you can’t choose when these jobs come around.)

Former Reds midfielder Alonso has quickly emerged as the favourite to succeed Jurgen Klopp, who announced last week he would leave the club at the end of the season.

“If he gets the offer, I think he’d be crazy personally not to take it,” Honigstein told BBC Radio 5 Live’s Euro Leagues. “I don’t think there is a better offer or a better job in the summer available than Liverpool.

“Even with all the legacy that might become baggage from Jurgen Klopp, you’re going to have a fantastic team and you’re going to be instantly competitive on all fronts.

“So, why wouldn’t you take it? The only reason he wouldn’t take it is he might feel he needs a bit more time, might want to play a first Champions League season, learn a bit more on the job.

“But, the reason I believe he will take it if it is offered to him is because I think he understands that Liverpool, for all their flaws and they’re not perfect, are a pretty stable environment under FSG.

“If you become a successful manager there, I think you have the chance to influence an amount of time that is hard to see in other big clubs.

“Real Madrid don’t think in these terms of somebody dominating an era. It's certainly not possible at Bayern Munch, not possible at Barcelona in the current guise.

“Liverpool doesn’t just offer the chance to win titles, but to be the main figure for five, six, seven, eight years if you’re successful.

“That’s why I think it will be the most coveted job for all coaches in the summer – and Alonso, I’m sure, will be very much top of the list when it comes to the contenders.”

The main issue, for me, is if he’ll take time away from Leverkusen to focus on negotiations and an offer from Liverpool, to sign a deal now, and then stay in Germany until the summer, and hopefully win the league. It’s not like he has to abandon the title challenge now; the same with other managers, who can complete their seasons.

But as with other options, if he doesn’t, it will be hard to move forward in time for well ahead of next season.

The Biggest Improver

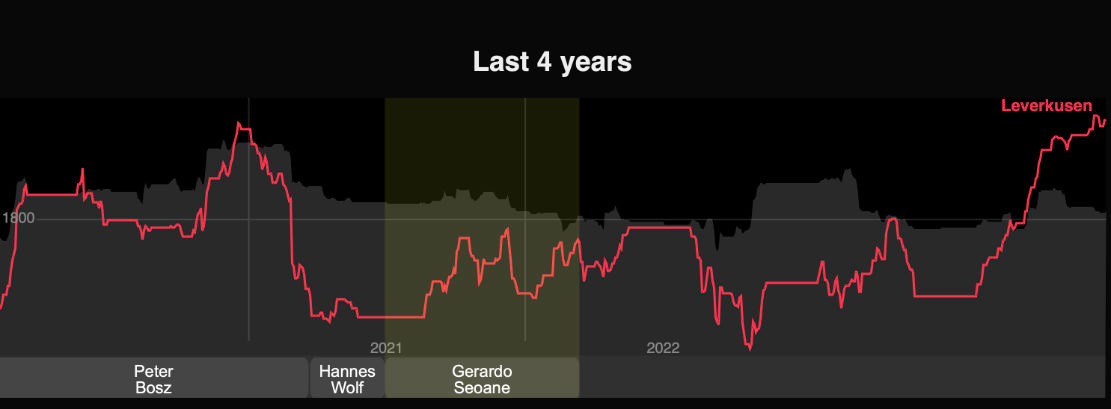

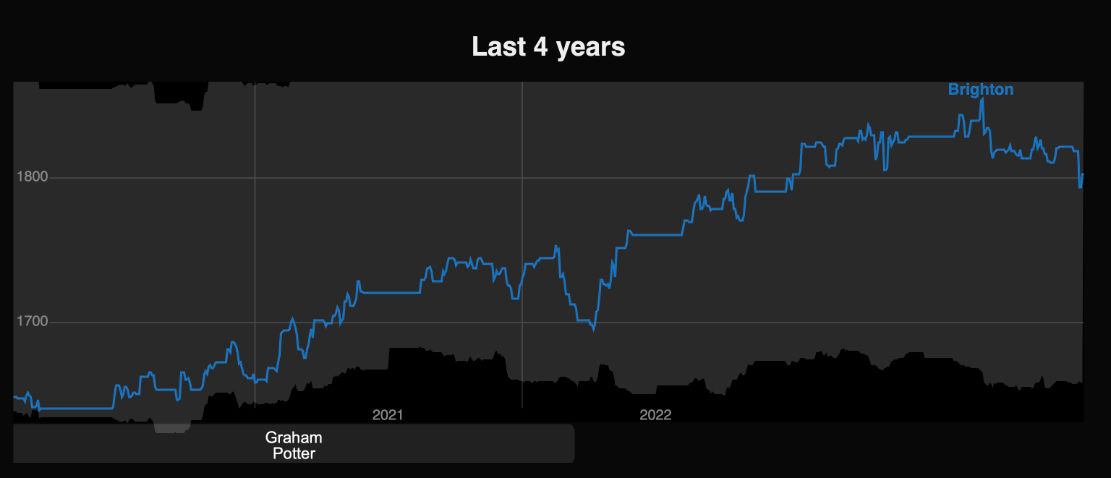

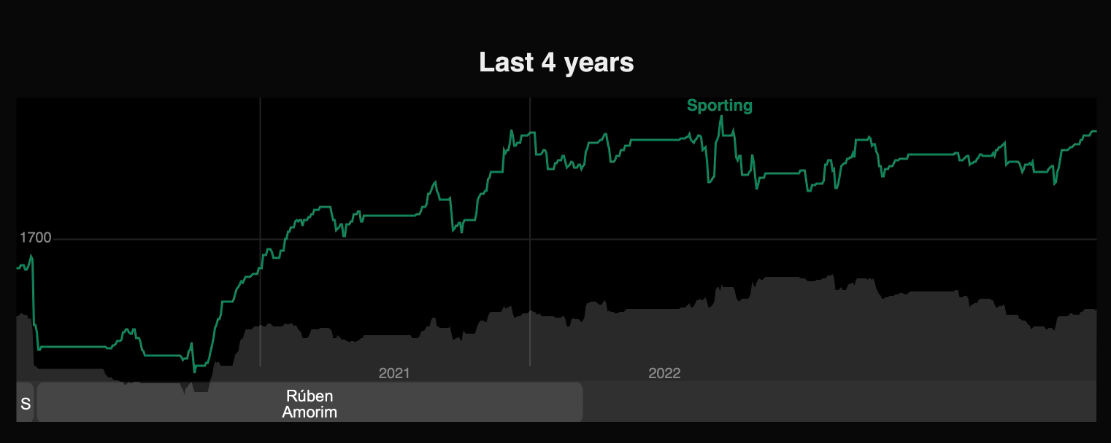

In the past year on the Club Elo Index, Xabi Alonso has taken Bayer Leverkusen from just below where Liverpool were in the final game of Brendan Rodgers’ reign (33rd), into the top ten. Up from 34th with a rocket.

This is league and cup and European form combined, albeit the Club Elo site doesn’t accurately show where Alonso’s tenure began, as it was later in 2022. (This seems the case with all managers on the site, which has accurate Elo data, but not managerial start points.)

Rúben Amorim and Roberto De Zerbi have also massively improved their clubs’ Elo rankings since arriving, albeit not the peak level that Alonso has; the other two have taken clubs from smaller bases to higher levels, but Alonso has taken Leverkusen to elite levels.

Rúben Amorim? In the last 12 months, Sporting have moved up from 32nd to 29th; in part due to the relative weakness of the league, and a less-stellar European record.

Two who aren’t even worth analysing are Andoni Iraola and Thomas Frank.

To me, any managers of low-possession, reactive sides with some similarities to a Jürgen Klopp team – in formation or pressing – is nowhere near enough, good though it may be for their current clubs. There are far too many differences, and a gulf in the proven level of experience required.

Leverkusen play ‘winning’ football, with 25 wins, four draws, zero defeats this season. That’s an 86.2% win rate, and a 0% defeat rate.

(Scoring more than 4x as many as conceded. That’s bonkers.)

Over a sample size of more than half a season, that’s elite; especially on the budget and based on expectations, and working from the position of inheriting a team in the relegation zone 18 months ago. As I said recently, it’s also not easy to continue to improve a team in your second season after the total break between seasons one and two, where so much can change.

While there may be some luck in a game or two where any club avoids defeat on an unbeaten run, one of the recent draws saw them have 30 shots and over 3xG (to a tenth of that conceded), and drew 0-0. Shit happens.

Hand In Glove

I’ve read some weird takes on Xabi Alonso, and how his football doesn’t fit this squad.

It does.

Indeed, like a glove – albeit a glove with extra fingers, as this squad is so multi-faceted, so you can mould it to fit; like the Swiss Army knife of gloves, for as many fingers as you require, if you’re freakishly many-fingered.

(Any excuse for a picture of the band Misty’s Big Adventure. )

And I’ve also seen him pegged as a ‘rookie’, who might not handle the pressure.

But he’s not really a rookie, is he?

He began coaching seven years ago; began managing five years ago; and began managing in the Bundesliga two seasons ago.

This latter part – ‘pressure’ – is where his time as a player also comes in. I’ve spoken about this before, but there are transferable skills from playing to managing, and this is one of them.

Because handling massive pressure (not only that, but year after year) is something Graham Potter never really had to do as a player, just like Roy Hodgson (another exported Scandi success story that didn’t translate well to a big English job), never knew pressure as a player.

(And yes, you can still feel pressure at a small club, a struggling club, but it’s not the pressure of expectation, and of the eyes of the world being on you. It’s different.)

Admittedly neither did the successful managers who never played at a high level (Rafa Benítez, Jose Mourinho, and to a slightly lesser extent as he was at least second-tier, Jürgen Klopp).

But they showed that they were totally ready as managers when they arrived in England for the first time.

Right now, there’s not really a Klopp, Benítez or Mourinho on the market in terms of what they’d done in the three years before arriving in England; and none of them had to replace a supremely successful, popular and charismatic manager.

(Claudio Ranieri was still a bit of a joke as the Tinkerman at Chelsea; Gérard Houllier had gone from hero to almost zero between 2002 and 2004 as his team, post near-death experience in late 2001, went from exciting to super-dull; and Brendan Rodgers was not exactly a hard act to follow.)

Lesser clubs rarely take the top titles now. Who has won all the recent German titles? Bayern. Who has won the recent Champions Leagues? Big English clubs, and Real Madrid, Barcelona and Bayern, going back a decade. Who wins La Liga? Real or Barca, almost always.

But Alonso is at least giving the Bundesliga a chance of a new champion for the first time since … Klopp.

Maybe the only manager to have both an impressive CV and not simply be part of the club system from which Liverpool could not prise a manager is Atlético Madrid’s Diego Simeone, with a title in 2021, but his peak trophy contention was almost ten years ago (a league title in 2014, and Champions League finals in 2014 and 2016).

He’s also not really the type of character you want (a winner, yes, and with charisma – but too volatile), and his football is more from the Mourinho, Benítez and Antonio Conte style of the 2000s and 2010s. He’s also got no managerial experience outside Spain and South America. I’ve not even seen him on betting shortlist.

Two decades ago, you knew that Benítez, fresh from winning two La Liga titles and a European competition in three years with the then-big Valencia (2001-2004); and Mourinho, from winning the league and Champions League with Porto (2004); and 11 years later; and Klopp, winning two titles and reaching a Champions League final (2010-2013) with the near-bankrupt Borussia Dortmund when he took over, could all improve teams and handle elite, title-winning and cup-winning pressure, but also produce some underdog upsets.

The didn’t arrive from tiny little clubs, bereft of pressure; they’d done that job years earlier, as part of their education. That was Klopp at Mainz, years earlier. That was Benítez at Tenerife. Mourinho at União de Leiria.

Klopp didn’t go from Mainz to Bayern Munich. Benítez never went from Tenerife to Real Madrid. They went to bigger clubs, but not straight to the biggest.

Liverpool are clearly bigger than any of Valencia, Porto and Dortmund (either now or then), but those were ‘big enough’ clubs at the time (and in some ways still are, although landscapes change and pressure changes with it).

They’re all historic clubs, who would perhaps rank in the top 20 for biggest clubs in the world, whereas Liverpool are contesting right near the top.

These clubs had won titles, and contested European honours, in the previous decade before Klopp, Benítez and Mourinho arrived. They just weren’t part of the very elite, in the way that Liverpool were (even in 2015), and even more so are in 2024. And they were at low ebbs or crossroads when Klopp, Benítez and Mourinho arrived.

Even before Klopp, Liverpool were ‘European royalty’, albeit a sleeping giant (not least when Hodgson was like football’s version of temazepam; insomnia was not an issue).

Like Leverkusen, these were ideal ‘stepping-stone’ clubs, where the pressure is big enough, but the expectations are not insane. You scale up in stages.

If you can win two titles with Valencia (Rafa) and Dortmund (Klopp), you’re close to the expectations at Liverpool.

Indeed, Benítez also winning the Europa League (Uefa Cup as it was) in a double in 2004, and Klopp taking Dortmund to the final of the Champions League (and nearly winning it against their richer arch rivals Bayern who disrupted Klopp’s squad on the eve of the game), showed the European pedigree too.

That’s vital; as I’ve said about Brendan Rodgers many times, he had no history of managing European club football, and his record in it (at Liverpool and since with Celtic) was terrible; and even worse, and which gets overlooked – Liverpool were poor under him in the league when also in Europe.

It’s a unique challenge, balancing both. It really is. It’s a super-important part of being a top four club.

You then need to be a good fit in other ways.

If you’re mid-table with Brentford, or have a good season with Fulham, or get Brighton into the top half of the table, that doesn’t really tell me anything about how they can handle what is a massive step up.

You can have bright ideas, but it’s a different job entirely.

Now, Alonso’s CV as a manager already has an unfolding title challenge 18 months on from rescuing a team in the relegation zone, and a Europa League CV (with a team who are ‘Europa League’ on budget) that reads 10 wins, two draws, two defeats; and this season, all six have been won, after a run to the semis last season.

But his experience as a player was almost 20 years of handling pressure, from his teenage years as a prodigy at Real Sociedad, a club big enough to have won back-to-back league titles in the early 1980s (and a cup in the late ’80s) but were 13th for three seasons in a row in the late ‘90s/early ‘00s – before Alonso helped drive that team to 2nd in 2003, as the captain, aged 21-22.

That’s pretty remarkable. That’s leadership, right there.

He had the pressure of it being his local, boyhood club, and his dad, as a player (before coaching), had won those two titles with Sociedad in the early ’80s (their one period of greatness) before winning another with Barcelona soon after.

That’s a childhood education in professionalism and pressure, followed by his teenage years in the Sociedad first team. Some players may never think like a coach or manager until they’re 35; Alonso was at the University of Football Thinking from the age of seven. You learn from those around you, even if you’re not consciously studying.

Handling pressure – being composed – is therefore transferable, but obviously if you lack talent, compassion, vision, communication and language skills, and various other assets, you may fail miserably as a manager; as many ex-players who could presumably handle the pressure as a player couldn’t prove themselves as managers.

Take Graham Potter again. As a player, eight Premier League games in the 1990s, and a lot of time in the second tiers and lower (West Brom, Birmingham, Stoke).

So, he understands players (of a certain level), and the many situations experienced on hundreds of matchdays, and then went away to coach for a long time.

I have full respect for his coaching journey, and he did improve Brighton after he arrived. But it wasn’t enough.

To me, his career is very Thomas Frank, and even more Roy Hodgson. Three managers who did well in Denmark or Norway or Sweden, and who generally had mid-table Premier League careers.

David Moyes is another, albeit without the Scandi sojourn (albeit he looks straight out of a noir thriller, possibly as the guy playing the corpse).

There’s just this weird thing where some managers guarantee you mid-table, irrespective of the quality of the team, in part due to mindset, lack of charisma and/or “don’t get beat” football.

They drag small clubs up to that level, and big clubs down to that level.

(I first came across the corner-shop and supermarket comparison 15 years ago, and began using it at that time. Most will only be able to manage the former.)

Potter visibly looked like he struggled with the pressure at Chelsea, and the players at that level of club saw a manager who had won nothing (besides the Swedish cup), and as a player done nothing (of note), and then on top of that, he seemed far from comfortable in his demeanour. He projected unease, awkwardness. Nice guy, but out of his depth.

Maybe Potter ought to have been given more respect. But ought to is often detached from reality. (I ought to have a full of head of hair.)

It didn’t help that the new Chelsea players hadn’t even heard of him; and while you can laugh at their ignorance of Swedish football and of an unfashionable Premier League team (plenty of them had just flown in from France), players are constantly testing managers to see if they’re the real deal, seeing what they can get away with, like toddlers constantly punishing the limits of their parents. Except there are 25 toddlers (or 45 in Chelsea’s case).

Starting with being a relative unknown makes life harder. You have more to prove. You have less leeway, less wiggle-room. Things can go badly much more quickly.

And it’s just human that if you’re 25, or even 21, you’d want to play for Xabi Alonso over Graham Potter, or Thomas Frank, or Andoni Iraola, or even Roberto De Zerbi (even if I think the latter has the personality and the style of play to succeed higher up).

Now, Alonso – as I was lucky enough to see in person – has taken a penalty in a Champions League final. (Okay, it was saved, but boy was he quick on the rebound!)

Indeed, he played in three Champions League finals, winning two. He played in, and won, a World Cup final. And also won two finals of UEFA European Championships with Spain.

That’s six appearances in the three biggest cup finals in world football (South American football would rank 4th, I’d say), and he five won. But even losing would have been an education in pressure.

Every single game was a test of his nerves, his character, his ability to think clearly amid the hubbub and chaos.

And he was a thinking player, not a running player, an athlete-player. He was the playmaker, after all; a footballing quarterback who needed to see the whole game. (And who used his skills to pass short, medium and long.)

He once said he never learned how to tackle, but his job for 18 years involved a bit of everything.

I lost count of how many other cup finals Alonso played in, but there are all the semifinals too. The quarterfinals. The massive head-to-heads, Classicos, derbies, Der Klassikers.

And he featured in almost ten proper title races as a player, for clubs – Liverpool, Real Madrid and Bayern Munich – where the pressure is huge; and it started when his Real Sociedad lost the title by just two points in 2003, winning as many games (22) as champions Real Madrid.

He was always a key player, the tempo-setting midfield controller.

He wasn’t a substitute goalkeeper, or an instinctive super-fast winger who never thought about the game, or an egotist superstar whose only concern was himself.

A lot of the onus was on him. And as a player he was the consummate cool, calm and collected customer, which is the style of the man as a manager, too.

“This is how a training session under Xabi Alonso goes - coaching in passing exercises & Co.”

I admit, I could just watch Xabi, in his 40s, take training. We could forget Anfield; build stands at the AXA.

Style of Play

Passing speed can be varied.

Passing talent is what’s required.

Passing direction and distance can be varied.

Passing talent is what’s required.

And Liverpool have an overflowing talent pool of passers, of all kinds, with many as individuals being capable of all kinds. You just tweak things on the training ground and evolve your own way, working with the strengths of what you inherit.

(Any new manager will have to adjust things to some degree, no matter what their approach has been in the past. This will be 25-35 new players to them.)

This from a Jonathan Northcroft piece in the Sunday Times shows the different speeds of passing and directness (this season vs last), but if Liverpool were to move closer to Manchester City’s style under a new manager I don’t see that as a problem. The club has the technical players to do so, but also can retain the in-built knowledge to play as fast and relatively direct as they do now.

I really like what Andoni Iraola is doing at at Bournemouth, but it’s done with an average of 44.3% possession. That’s not enough evidence that you can play possession football and not just press and counter-attack. And again, although he had a full career in La Liga as a player (and seven caps for Spain), managing Rayo Vallecano, Mirandés and AEK Larnaca is a good coaching journey, full of types of education – but in no way comparable to the job of managing Liverpool. His Rayo Vallecano team did well but also averaged only 47% possession.

To me, these days, averaging even 55% possession is relatively reactive football (especially for a big-budget/Big Six team), and sub 50% is hyper-reactive.

(When I checked average possession figures for the last few years in the Premier League, there seemed to be a relative chasm between 54% and 58%; an odd void.)

The new Liverpool manager needs to show that his teams can control games with possession, as well as doing well without the ball. There are some top reactive managers out there but proactive football has to be on the CV.

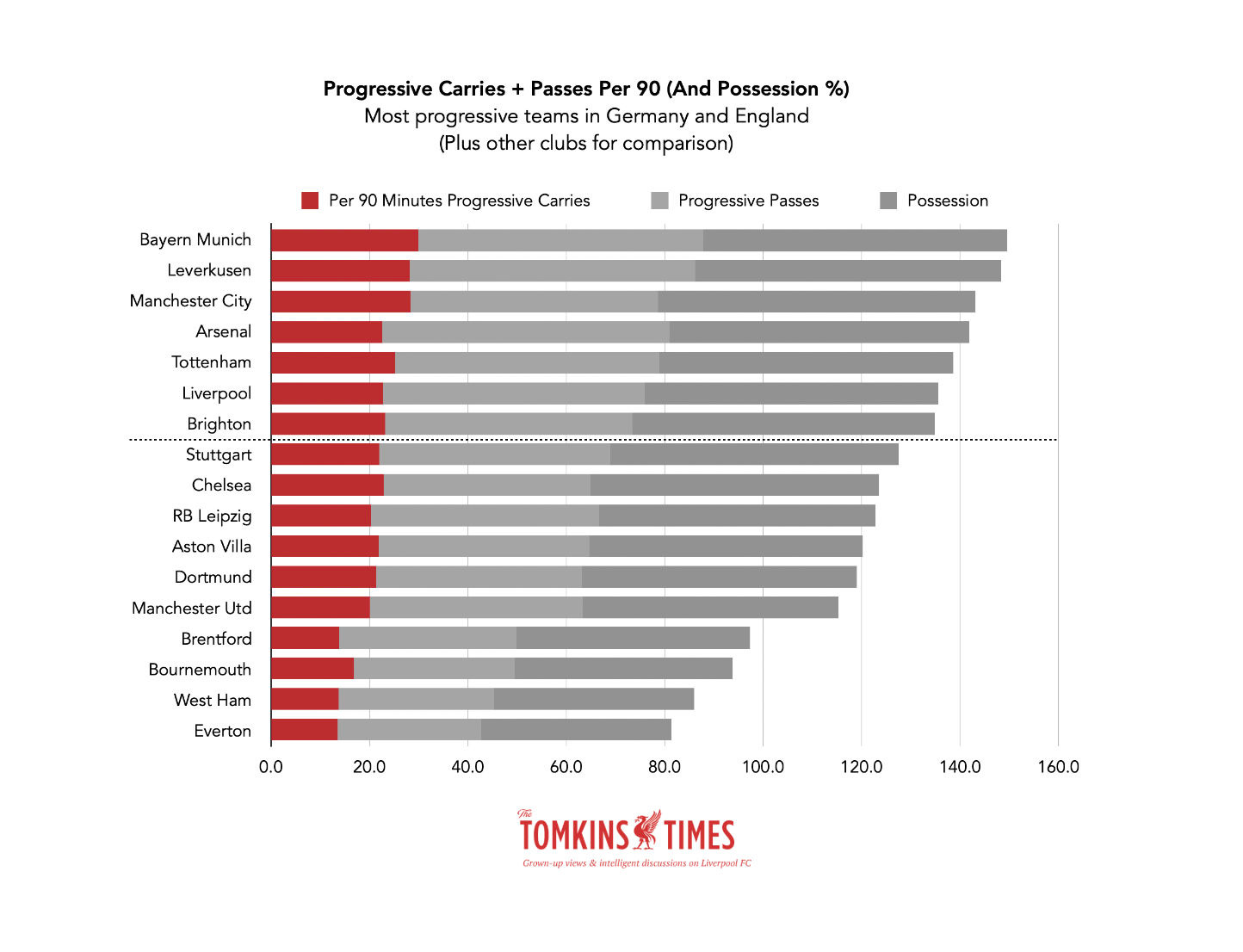

While I’ll use Mizgan Masani’s graphics to illustrate various aspects of team styles later in the article, I want to start with one of my own.

Now, it’s perhaps not the done thing to add two quantitive metrics to one of percentage, but it all adds to the picture: how much possession does the club have and how progressive are they with it, both with carries and passes? You can add that all up, and I think it passes muster.

If you compare Brighton and Leverkusen on this chart, you would not know the were lower-budget teams of outsides.

Everyone down to Stuttgart plays in an ‘overall’ similar way in terms of possession dominance + progressive carries + progressive passes, within which there will be differences on emphasis, attack speed, use of wings etc.; but all those can change within games or from game to game, or from season to season.

(Look at how differently Liverpool can use the flanks with Conor Bradley and Andy Robertson compared to Joe Gomez and the now-inverted Trent Alexander-Arnold. Meanwhile, Man City’s possession figures have shot up since Erling Haaland was injured, as have their points per game, which was lower than usual in the league last season, and this season until he got injured. They’ve been successful both ways, but have to play differently with Haaland to without him.)

Bournemouth and Brentford don’t play anything like Liverpool when you mix progressive actions with possession. Again, maybe they could with better materials, but Roy Hodgson couldn’t, David Moyes couldn’t and Graham Potter couldn’t. Again, is, not ought.

While Liverpool can still play ‘heavy metal’ football, it’s less all-out thrash these days (and has been since 2018) and more melodic, with shifts in tempo and orchestral flourishes.

It’s more prog-rock, if you will.

(My favourite ever prog song/recording linked to! You don’t have to agree, but I think it does just about everything. I also love 2-minute indie songs, but they don’t fit the metaphor.)

Or, to give it it’s full name, progressive rock: shifts of tempo and dynamics. To me, Leverkusen play prog-rock too. Just in a different way.

Progressive football.

With pace. And the ability to hog the ball for long team solos.

It’s not ambient jazz, or ukulele music, or Phillip Glass.

But what we can also see, later in the piece from Mizgan’s analysis, is that all three of the main contenders’ teams play football in a similar way to each other. So “fit”, authority, fan buy-in and player buy-in become more important.

De Zerbi would also worry me a little in terms of volatility. Klopp was volcanic, but mostly on the sidelines; never behind the scenes.

While Klopp gained more control of transfers, he never fell out with the owners. He never made excessive demands. He knew the score.

Creative differences (another theme with bands, prog-rock or otherwise) emerged with the Directors of Football, but I personally don’t mind that if it comes after years of success, and not before success can even flourish (as happened with Brendan Rodgers and the transfer committee, as it then was).

Klopp understood the way FSG worked, the budget, and not spending what the club doesn’t have; something I’ve pointed out as essential since 2015, and now you see it coming home to roost for other clubs, at a point where Liverpool’s squad has never been better and FFP is not a concern.

Klopp came from Dortmund, where the budget was limited (having been non-existent at first), and Mainz, where the budget was also non-existent. He wasn’t a Mourinho or Guardiola, who, though elite in their peaks, had always had the best players to choose from, and the money to solve any issues.

(Once Mourinho had less money, he became a Europa League manager, and then a Europa Conference League manager, where they had to invent a total middling trophy just so he could act like he was still a “winner” with the Italian giants Roma).

And FSG always put the money into the less-visible wage-bill (with incentives based on what the club earns via on-field success), and not just transfer fees.

Klopp took things to the next level with a no-dickheads policy, which seems the opposite of what they’ve done at Manchester United, where the disciplinarian coach (whose approach seems a bit too counter-attacking for a big club) is struggling with half-hearted players causing all kinds of off-field incidents; but in his own case, he paid £80m for one of them (Antony).

Their top earner and star players goes on benders and phones in sick for training; albeit unlike a £73m player they’ve shipped out on loan (and who had massive issues with turning up on time, or turning up at all, before they signed him), he did at least take responsibility, which you’d hope included an apology. However, that’s a mess of a dressing room. (Albeit that’s their issue to sort out.)

Then, only the players with the most talent, consistency and the best attitudes get the biggest bucks at Liverpool; never a new player, or a young player, or an older big-name signing who is past his best.

(One slight exception was Thiago Alcântara, and I don’t think anyone who has played or trained with him would begrudge him a penny, even with the frustrating injury record. And he was vital in 2021/22, which was actually Klopp’s best-ever season overall; true greatness denied in part by Liverpool fans being gassed and kept out of the stadium in Paris, and losing the title after Paul Tierney – damn it, I mentioned him again! – didn’t give Everton a blatant late handball against Man City.)

The club even massively cut what it pays Academy players a few years ago. Result? Players who want to play football, not own Ferraris.

There were far better players out there aged 16 than Conor Bradley, but Bradley had the attitude, desire and humility to succeed.

League of Nations

Another interesting point is that Liverpool’s current squad is not “German”, so it’s not set up just to match Klopp; unlike how it was fairly French for Gérard Houllier and reasonably Spanish for Benítez.

If anything, it has a bit of a Dutch tinge with Pep Lijnders perhaps having some influence on the signing of Cody Gakpo, Ryan Gravenberch and Sepp van den Berg (doing extremely well on loan in Germany), with Virgil van Dijk obviously the Dutch standout not connected to Lijnders.

It’s almost like a League of Nations at Anfield, with an increasingly strong homegrown core.

But Alonso speaks Spanish (obviously), German and English, and possibly about 83 other languages.

There is also Portuguese thread to the squad, with Jota, and then Díaz and Núñez signed from Porto and Benfica respectively.

But even the Portuguese-speaking Brazilians have now mostly left. Alisson aside, the native tongues of the South Americans are all Spanish, albeit English should be the language of the AXA and Anfield.

Half a dozen of the squad were signed from Germany, but none are German. Three were signed this summer from the Bundesliga, but by then, it was Klopp and Jörg Schmadtke leading the process, and thus the first time it heavily tilted in that direction.

But even then, it was a Hungarian, a Dutchman and a Japanese. (None of them walked into a bar.)

Each had experience of other leagues. Each speaks excellent English. (And the one German player the club has played for Cameroon.)

I’ve said before that Alonso knows Thiago Alcântara well – they shared an awesome midfield for Bayern for a few years.

I don’t see a lot of other pre-existing relationships between prospective managers and existing Liverpool players, and even Thiago could well be gone by the summer. So that might be moot.

(I’ve suggested Thiago before as a possible coach, but he may want to play on elsewhere instead; but he’s good enough, when fit, and unique enough, to keep, albeit on a reduced wage. I don’t know if he could be a player-coach, but I think he could help build Alonso’s style from the training pitches.)

Indeed, whoever comes in may choose to add a coach with recent Liverpool connections, to complement what will be a reasonably big staff of their own. (James Milner is someone I thought would stay and eventually take up a coaching role.)

“Fit”, and Experiential Diversity

Mikel Arteta seemed suited to Arsenal as he did his coaching badges, and then his hands-on coaching experience, at Man City – a more successful club of late than Arsenal.

While never an Arsenal legend, he was club captain; a thinker on the game, from the same youth system as Alonso and the area of Spain producing so many top coaches, and who did enough of an apprenticeship alongside Pep Guardiola.

Arteta’s playing experience took him to four countries, albeit he didn’t play in a lot of big games (certainly when compared to Alonso), with only a couple of cup finals at Arsenal. The pressure at Rangers will have been big in the Glasgow bubble, albeit in a weak league.

But he had a good top-level career, and everything was set up for Arsenal. Expectations were low, and they had young players to build with, and overpaid high-profile dickheads and faint-hearts to ship out (which I felt make sense, despite some Arsenal fans disagreeing).

He had no managerial record, but he had ideas, and was respected. That’s half the battle.

And he had the power and wisdom to oust the big-name players who undermined him; another essential quality, albeit one often needed earlier in a tenure when they are someone else’s buys and you need to stamp your authority on a club.

He has a real arrogance about him, that I’m sure the Arsenal fans like. I find him quite obnoxious, but that’s fine if he’s in your dugout. He won the FA Cup early on, and in over four years has had one tilt at the title that ended up faltering quite badly a dozen games before the season’s conclusion. They’re back in this one, albeit have a far harder remaining fixture list to deal with than Liverpool.

He’s been a very good appointment, if not yet a runaway success. (And he was very pleased at beating an under-strength Liverpool at the Emirates at the weekend.)

Back in 2020, Unai Emery – another from that hotbed of coaching talent – had a better track record as a manager, and still has won a lot more; but as I noted before, Emery was a bit skittish, nervy and unclear at Arsenal.

He was too technical for egotistical players who were too lazy to listen. He didn’t have the “fit” that Arteta had. While he won everything at PSG, who didn’t? And Emery also partly failed there too.

Emery seems perfectly suited to a ‘fairly big’ club like Villa with some underdog status, which is a level where I think managers like Potter and others should have stepped up to (like Eddie Howe at a now-rich Newcastle, who were still a long way from success), rather than going straight to the Big Six.

One point I keep reiterating is that playing midweek European games and then being expected to win at the weekend is a totally different challenge to playing 40 games a season. I see this as a vital point for analysis.

VITAL!

To have the experience to balance that is essential; and while Emery frequently won the midweek European games (and competitions overall), his teams suffered in the league. But no one cared too much, as it was Sevilla or Villarreal, and finishing 7th wasn’t a big issue.

Yet no one this season in all of Europe has done better with Europe-to-league balancing than Alonso. Few can match his 100% win rate in Europe this season, and no team in the main leagues has a better points-per-game tally. Even Man City can’t match that.

At City, Pep Guardiola “fit” simply because they’d spent years bringing in all his favourite people, who would get his favourite players, ahead of his own arrival; and then gave him lots of money to spend, to further shape the squad. And he had a mixed first season, before things settled down.

Originally, Frank Lampard was actually a good “fit” for Chelsea in terms of fan adoration, but he was a manager low on experiential diversity.

You could argue that the 279 managers he played under at Chelsea brought every flavour, but like Steven Gerrard, it was a career mostly at one English club, then a bit of time in America at the end.

Lampard has managed English clubs only, and even had an 11% win record in a second spell, as caretaker.

Before he arrived at Chelsea (the first time) he’d done just a year with Derby. That was it. Now, that is untested.

That said, Chelsea had a transfer ban, and in two years he brought through or trusted more young players than it seemed the club had in two decades, and his time also coincided with the pandemic.

I don’t particularly rate Lampard as a manager (he remains utterly unproven), but to manage during a transfer ban with your two years covering almost the full first year of Covid-19, must have been challenging.

It felt like he was at least building something with all those young players; players often subsequently sold for the pure profit they make on the books, so the club could spend like maniacs on a random assortment of 20-year-olds with potential and no shared culture, experience or cohesion, yet still racking up tons of debt.

A lot of the squad of 2019/20 (who were under 30 at the time and thus still in their prime) are doing well all over Europe right now; much better than Chelsea, in fact.

My point here is an example of how “fit”, even without much clear managerial or coaching excellence or even experience (one season), was still better for Chelsea than the 430 games of management from Potter, whose win percentage at Chelsea (38.7%) was considerably lower than Lampard’s first spell (52.4%), but fairly consistent with Potter’s own low win percentages with Swansea and Brighton (both low 30s).

Again, there was this impression that Potter would do better with better players (and that, as an English boss, he’d “earned” the right), but like Roy Hodgson he was tied to the levels of the past. (Is, not ought.)

Potter also had a tough task, at a club that was acting in various insane ways, but he projected the air of a middling office manager whose name no one can quite remember. (“Alright Dave!”) Indeed, the players mockingly called him Harry.

What Potter never presented was winning football. Ditto Hodgson, Moyes, and various others.

It was survival football, status quo football (no, not the band albeit he mirrored its form of bland rock), and full of limits that he’d yet to prove he could burst through.

When Lampard first arrived at Chelsea he was on the up; unproven, yes, but on the up. There was a buzz from the fans.

When he returned, for 11 games, he was on the slide. The fans still loved him, but he won one game. He was a short-term caretaker and everyone knew it. It never turned toxic as he was one of their own, as they say.

Perceptions are important, and players and fans buy-in to success, or improvement. They are not very trusting of those on a downward trajectory.

Do you blindly follow a leader into battle after several successive failures? Perhaps we put too much stock in recent success (recency bias), but the ‘vibes’ are important.

“Show us your medals” is a famous cockstrut in football. To have no major success as a player or a manager makes it harder to win over doubters.

You’re then just down to your ideas and your personality, and 25 players trying to suss you out.

A few years ago I looked into the record of countless elite managers who had returned to clubs where they’d had success to manage for a second or third time, and almost always the win% dropped, and they failed, and failed again.

Bar the odd exception, like Jupp Heynckes at Bayern Munich, the trend was downwards almost all the way. (I’ll revisit and update this soon, as it’s interesting stuff.)

The energy they bring back is different.

Most managers who win the biggest trophies do so within a ten-year window. Coming back, they’re possibly on the slide, and the club is usually in panic mode. Expectations are different, and there are almost always caveats around their return. (The Italians call it ‘reheated soup’, apparently.)

It just shows how the same manager never walks in the same river twice, because he is not the same manager and the river is not the same river; as Heraclitus famously said about Lampard.

But a manager arriving on the up (or just having had a brief blip, like Klopp did in 2014/15) is different.

And they still need to “fit”.

Ange Postecoglou was a bit of a left-field appointment by Spurs. But his football promised to be exciting, after the turgid mess of Antonio Conte, whose turgid mess followed the turgid mess of Jose Mourinho; two anti-football managers from a bygone era whose labels as winners were as out of date as the flares I’m now wearing.

Postecoglou fit precisely because the previous two managers were such terrible fits, despite stellar trophy hauls in the past. (They then got a great start partly because they played the worst teams in the first few games, plus Liverpool, who they beat ‘unfairly’.) Postecoglou still feels like a good fit, and Spurs are doing well enough.

Steven Gerrard was hounded out of Villa for far less of a bad run than Lampard’s final 11 games, but Gerrard never “fit” at Villa. The fans accepted him at first, but never took him to their hearts. There was no connection to Gerrard when times turned rough; and Gerrard’s entire DNA as a manager was tied up with Michael Beale, his assistant, who left. Villa then crumbled.

Gerrard had the cachet, the medals, the stature, but not the full range of skills; once Michael Beale left Villa, Gerrard was exposed. While all assistants can be important, if you rely too heavily on yours, your fortunes can change when they move on to something else.

And weirdly, the timing that made Alonso think Gerrard would manage Liverpool before him, as stated six years ago, now has Gerrard scrabbling around in the the Saudi sand. (Gerrard would perhaps make a great no.2 on paper, but it would be a step down from management, and also, you perhaps don’t want your no.2 to bring about too much focus. Alonso also has his own no.2.)

Five years is not just a long time in football management, it’s essentially a ‘generation’, as tactical ideas evolve much quicker thanks to technology. Five years ago, Gerrard was flying high with Rangers.

Then, look at Chelsea. While I’d never take the League Cup final for granted, Mauricio Pochettino hasn’t done very well, has he?

But he did have a good track record.

However, five years in football is enough to see a full cycle of managerial styles end and new ones emerge (with ten years, as noted, the usual span of major honours); and his best work was between 2014-2019. I think he did a great job at Spurs, despite winning nothing; he took them very close, and they were consistently good.

But was he a good “fit” for Chelsea? Is he still an elite manager or just beyond his peak? He looks older, shabbier. More worn down. Less energetic.

When I was fully onboard with a return to the Reds of Kenny Dalglish as caretaker, pushing for it in late 2010, Dalglish had been out of the game roughly as long as the time between Pochettino’s appointments at Spurs and Chelsea. Dalglish, while no longer cutting-edge, was a perfect fit, and did the perfect job as caretaker, to lift the club from a relegation battle into the top six (he was already back at the club working at the Academy, which helped).

The issue was that he then became hard to move on from, and the next season wasn’t great; albeit a lot of good things happened, including the settling in of Luis Suarez and Jordan Henderson, two cup finals (one won), an almost Darwinian ability to hit the woodwork; plus, it was no longer as toxic and negative as it had been under Hodgson. But clearly Dalglish was no longer an elite manager, and to me, an ideal morale-booster when appointed.

Dalglish was undoubtedly in part a sentimental move, and it worked, in a limited way. But my fear is that Liverpool are scared away from Alonso because of a sense that feelings might be overriding logic. Almost a fear to go for something so obvious that would seem too obvious.

However, I think Alonso is logically elite, and on the rise.

Go back five years, to 2019, and to me, Mourinho was “gone”; a lot of people didn’t realise, but his football looked dated.

Go back five more years, though, and Mourinho was still elite. Just. But even around 2015-2016 you could feel things were unravelling more quickly for him at clubs than in the past; and while he won the title again with Chelsea, his overall record second time around was worse.

While there are exceptions, the major trophies* are mostly won by managers within a ten-year window. Klopp’s ‘majors’ are two Bundesliga titles, in 2011 and 2012, and a Champions League with Liverpool in 2019, and the league title in 2020.

(* Domestic title and Champions League, in main five leagues.)

You could argue that he’s now outside that ideal window, albeit the refreshing with Lijnders half a decade ago or more could do what the changes did for Alex Ferguson, and 2021/22 was excellent, as is 2023/24 so far. But Klopp has admitted that he’s tiring.

Again, some managerial qualities can remain consistent.

And you can gain more knowledge, wisdom and grow in stature, whatever your age.

But perceptions can change, as can the game around you, and your tactics can date. You’ll only get older and older as the players stay roughly the same average age. You run out of energy, start looking old, feeling the toll it takes. You’ll look more like a granddad than a cool older brother. Once you’re sixty, you’re indeed old enough to be some of the players’ grandfathers.

The next wave of coaches sweep you away from title-chasing teams to Europa League sides, then you’re mid-table somewhere and wondering what the hell happened. Few outlast a decade at the top; those who do evolve and have staff that evolve with them, and the budget to constantly overhaul.

Alonso is part of that new vanguard, ready to sweep the old guard away.

In fairness, so are his rivals.

Rivals

But I still don’t see much about them that makes them stand out more than Alonso; indeed, more than makes them seem less complete in terms of all boxes to be ticked.

Rúben Amorim is doing extremely well in Portugal with Sporting Lisbon. Good manager, clearly. Could be elite. But to go back to an earlier point, where’s his diversity of experience?

He’s from Portugal. Played for four clubs, all in Portugal (bar a dozen games in the time-waste zone of Qatar). Played for Portugal.

Has managed four clubs. All in Portugal.

Rúben Amorim might be a good choice (clearly he’s got something about him), but to me, the only thing I can say for sure is that he’s a great choice for Portuguese football at this point, aged 39.

Also, his record in the Europa League is nowhere near as good as Alonso’s in the past two seasons; four wins from 12 games, compared to Alonso’s 10 from 14. (Amorim’s other two Europa League games saw him lose in the qualifying round.)

Of course, Klopp only had German experience. But Klopp is Klopp; if Rúben Amorim can match Klopp’s talent with Klopp’s charisma, and Klopp’s ability to connect with the fans, great.

But Klopp had also taken Dortmund to the Champions League football, beyond the double titles, that themselves were more outlying than one of the big Portuguese clubs winning the Portuguese leagues. Amorim’s European record is not so special.

In 28 games, he’s won just 35.7%.

De Zerbi has won just 33.3% of his 12 European games.

Alonso has won 71.4% of his 14.

These are small samples, in different contexts. But evidence, all the same.

Amorim’s full European managerial record is 14 games in the Champions League and 14 in the Europa League, with five wins each time; losing seven in the main competition and three in the Europa. Even though it’s a small sample size (28 games), he has never taken a team as far in Europe as Alonso took Leverkusen (semis) last season.

Alonso has already won two more European games as a manager than Amorim, in just 18 months, and half the number of games. And Alonso has done so while maintaining a scorching domestic pace.

De Zerbi is finding life harder in the league with Brighton this season, as expected. His one season in the Champions League, with Shakhtar Donetsk, saw zero wins, and two draws; finishing bottom, below Sheriff Tiraspol. But Brighton have won four of six in the Europa League this season; meaning four wins from 12 European games in his career. He seems to be improving, in fairness.

So while these comparisons span different competitions, there’s a sense that Alonso “can do” Europe, where the others are yet to convince; and Alonso “can do” Europe+Domestic.

De Zerbi is also the only one to manage in the Premier League.

He also has a far better diversity of experience than Amorim, playing in two countries and managing in three so far. That said, Shakhtar Donetsk are almost a one-team league in Ukraine, with 15 league titles in the past 20 years; and had to leave before his one full season (in which they were top) was concluded.

But his English is not as good as Alonso’s. (Rúben Amorim speaks English, albeit I’m not sure how well.)

Alonso has yet to win anything, but has a great chance this season. And it’s not like winning the Portuguese league with one of the big clubs, who share it around.

But again, even if not (Bayern’s squad is insanely big and expensive and they have a top manager, not a bumbling rookie), to take a team like Leverkusen to win close to 90% of games in all competitions whilst scoring four times more goals than conceding screams of a genuine achievement; far more so than, say, winning four or five random domestic cup games that may be against lower division teams and getting a silver trophy.

If you manage in Germany, you’re unlikely to win anything if you’re not at Bayern Munich.

Even Klopp found that, after 2012. They just take everyone else’s best players.

I wouldn’t be disappointed with either of the two main alternatives to Alonso, and I’d get behind whoever is appointed, assuming it’s not someone clearly unqualified (which seems unlikely). And I’d still reserve judgement. But Alonso ticks the most boxes.

To end, here are some tactical comparisons, but to me, it’s all much of muchness, in a good way.

Tactics and Team Data

What’s interesting is that Alonso, Amorim and De Zerbi’s teams possibly have more in common with each other than with Klopp’s Liverpool, but we’re talking about progressive, high-possession, hard-pressing football in all four cases.

It’s like the genus of big cats (genus Panthera), with Cheetah, Puma, Leopard and Jaguar, with different attributes, but within an overall type; there are no elephants in this room.

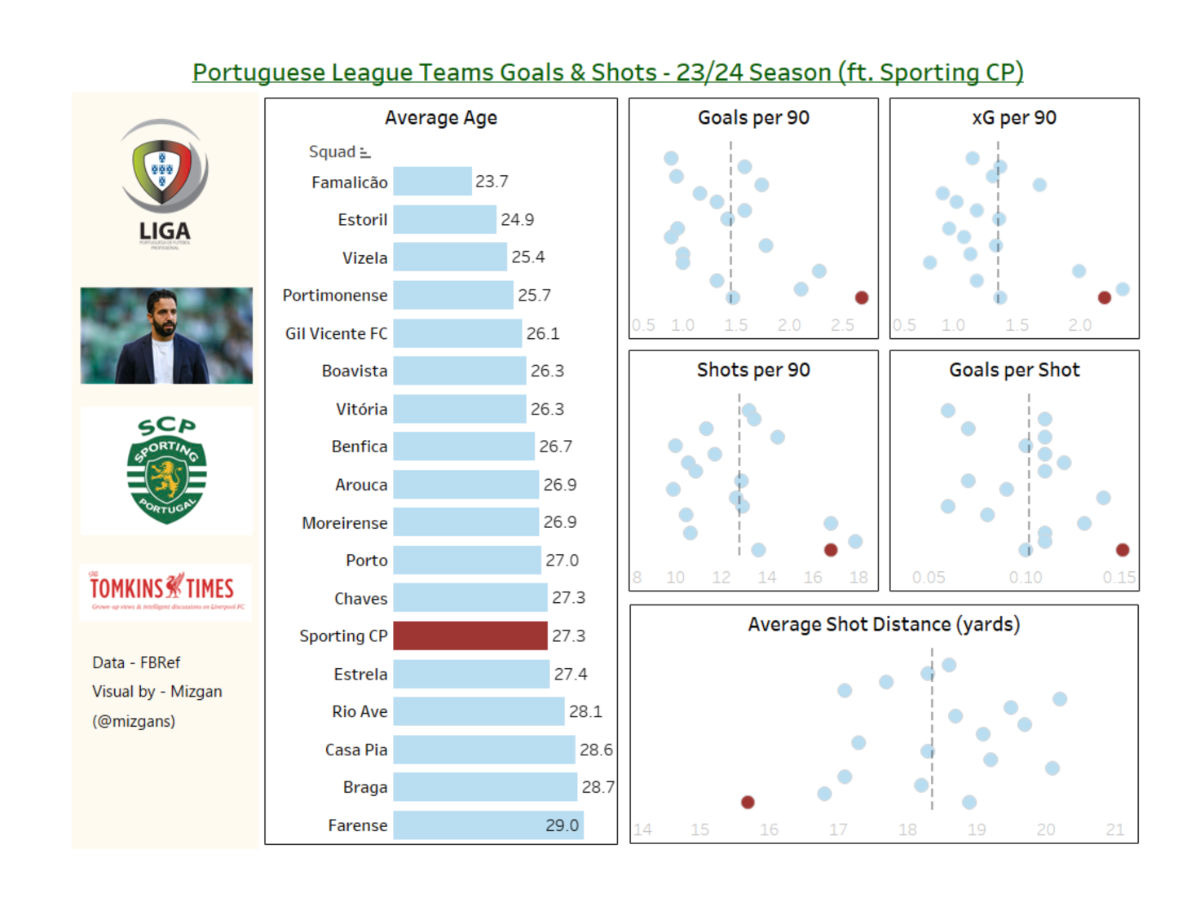

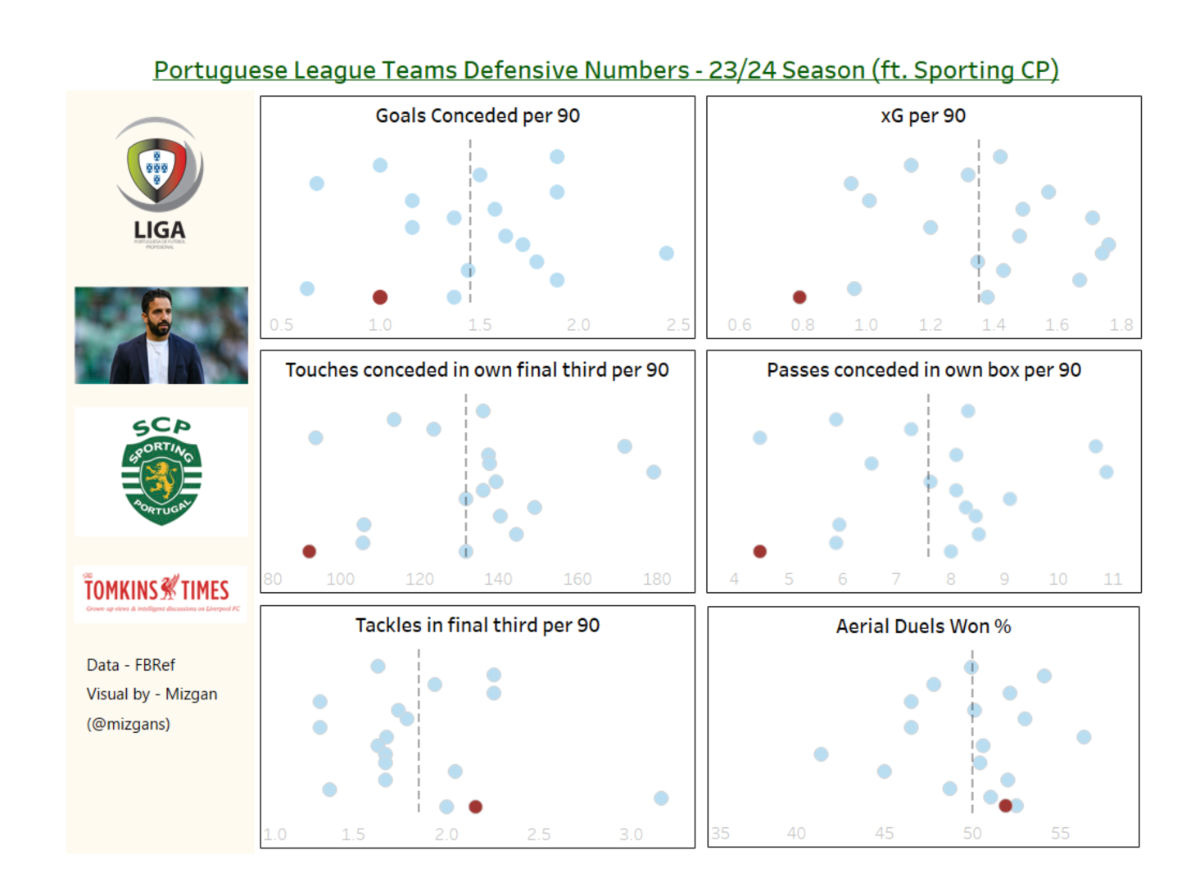

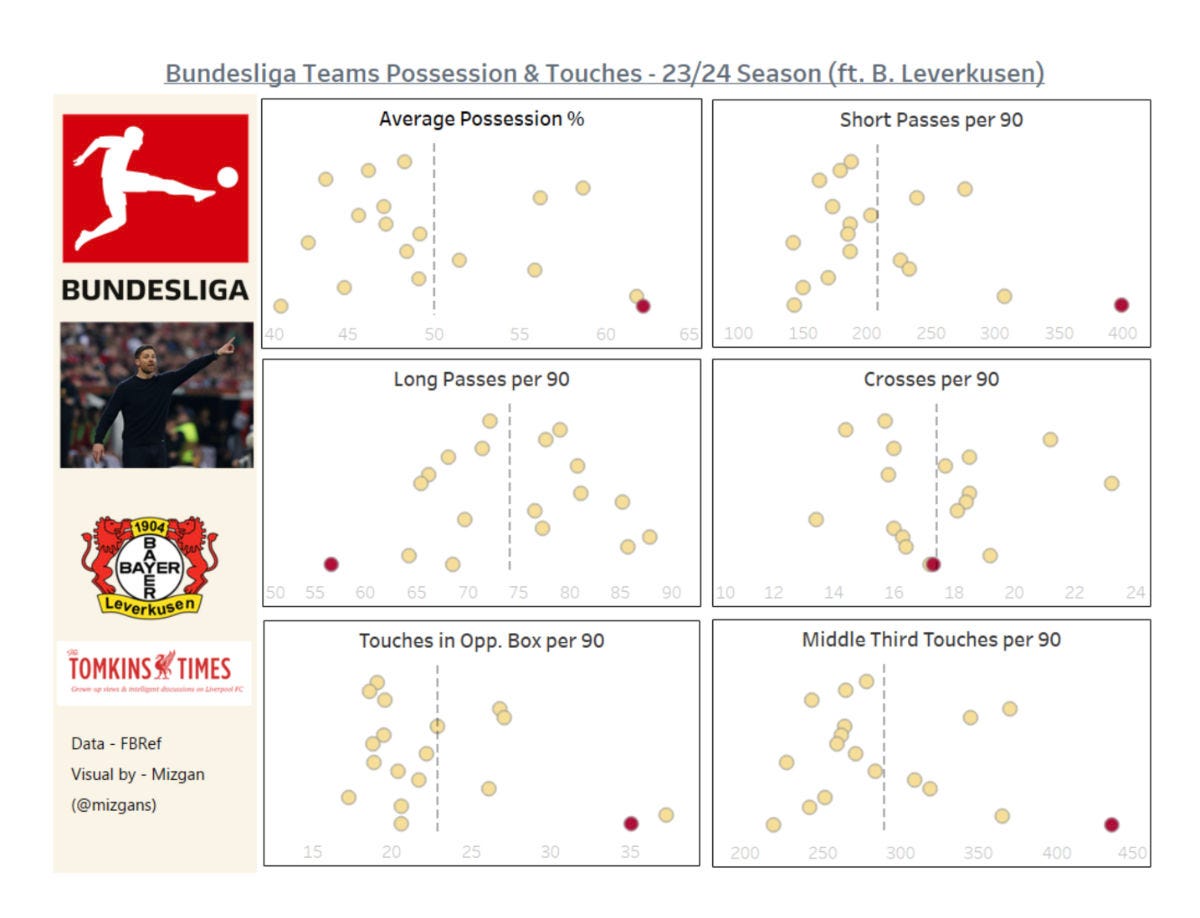

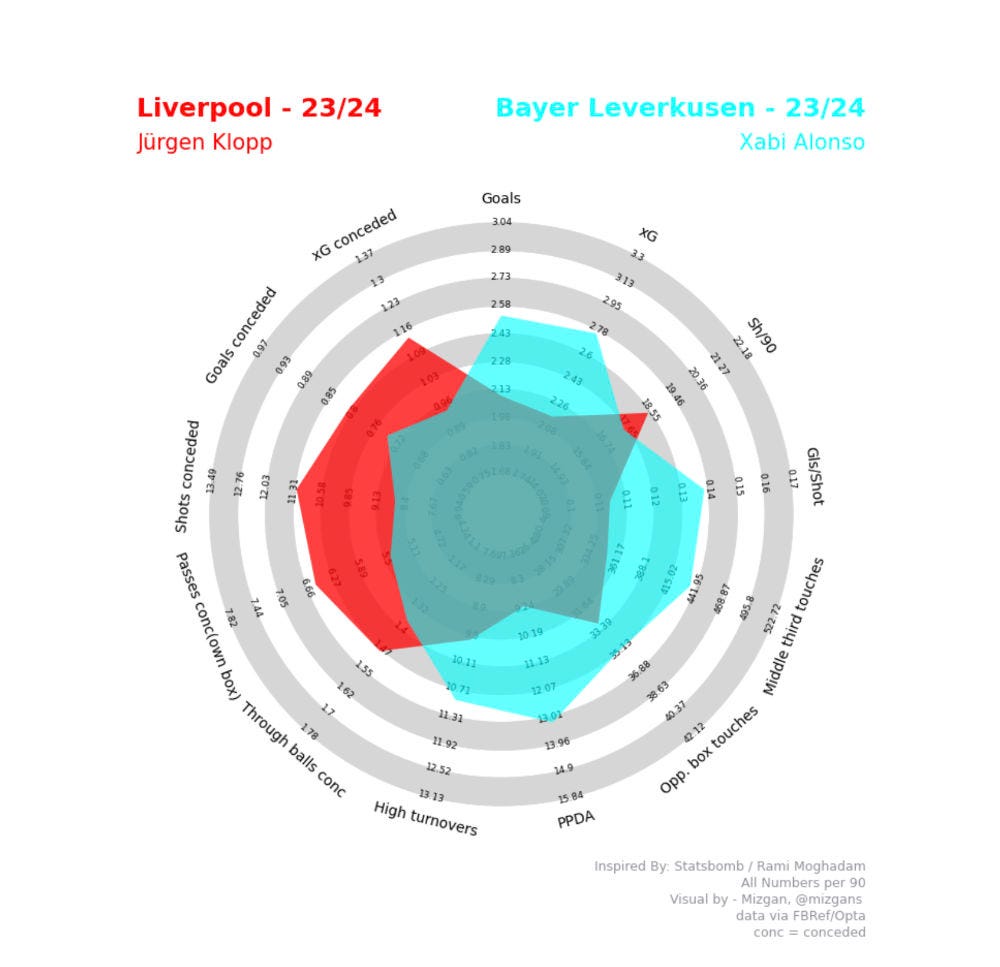

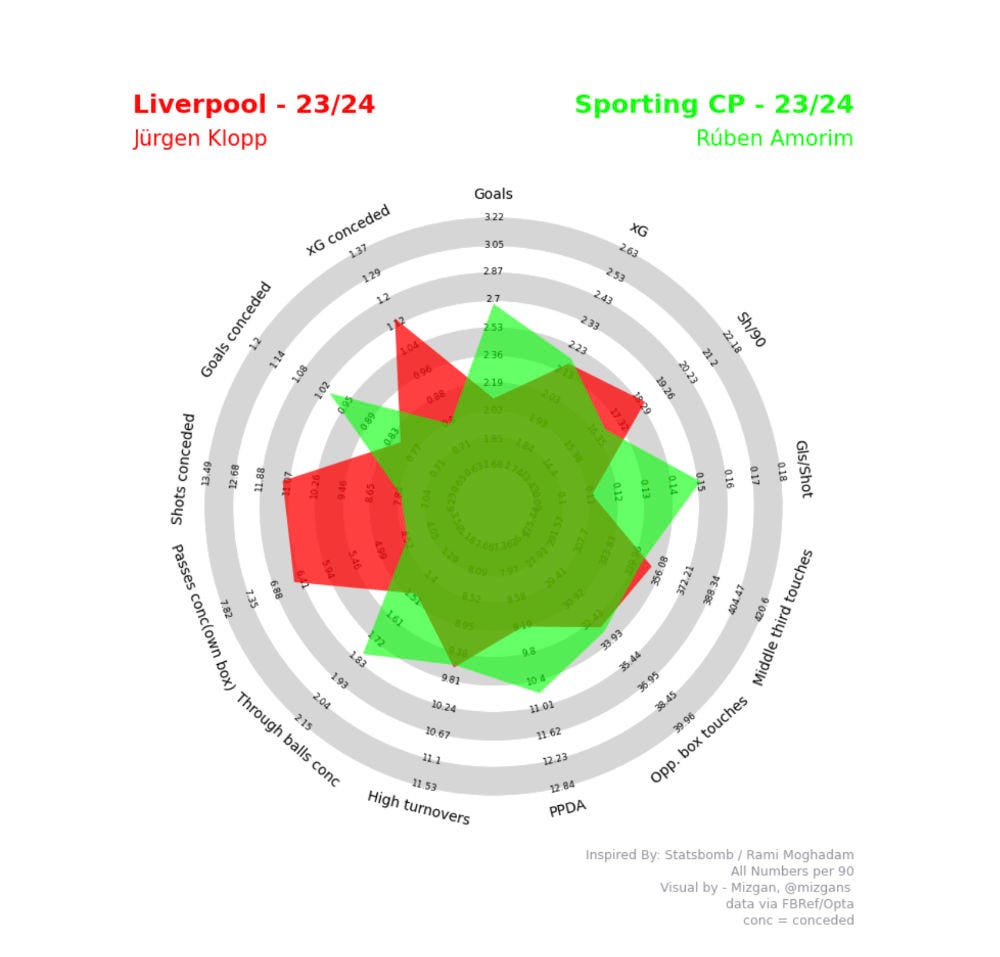

There are three dashboards Mizgan has provided for each club: goals/shots, possession/touches and defence (numbers as of 29/01/2024).

His comments are in italics, mine are as normal.

Sporting CP

Amorim is only 39 and has age on his side just like Alonso (42). Amorim also prefers to play the 3-4-3 system with marauding wing-backs, a double-pivot midfield and a narrow front-line.

Amorim’s team are the best in goals scored and quality of shots (aka goals per shot). They are second-best in xG creation and shots attempted. Lastly, they do not like taking a lot of shots from far out, hence low average shot distance among teams in the league.

This is actually the exact opposite of Liverpool, who shoot from joint-furthest out in England, at 18 yards. Also, a lot of efforts closer in can be headers, which are obviously harder to control than a close-in shot where the ball is on ground, if under control.

Just like Alonso’s Leverkusen, Sporting, under Amorim, prefer to keep the ball, play loads of short passes, have plenty of touches in central areas to dominate games and flood bodies in the opposition box. They use crosses a lot more compared to the German side though.

Although they have the third-best defensive record in the league in terms of goals conceded, xG concession, touches conceded in own final third and passes conceded in the box numbers show that they are very good off the ball in general (second-best in total high-turnovers so far too: 182, 9.58 per game).

All in all, they can count themselves a touch unlucky to have a goal concession rate of close to one per 90.

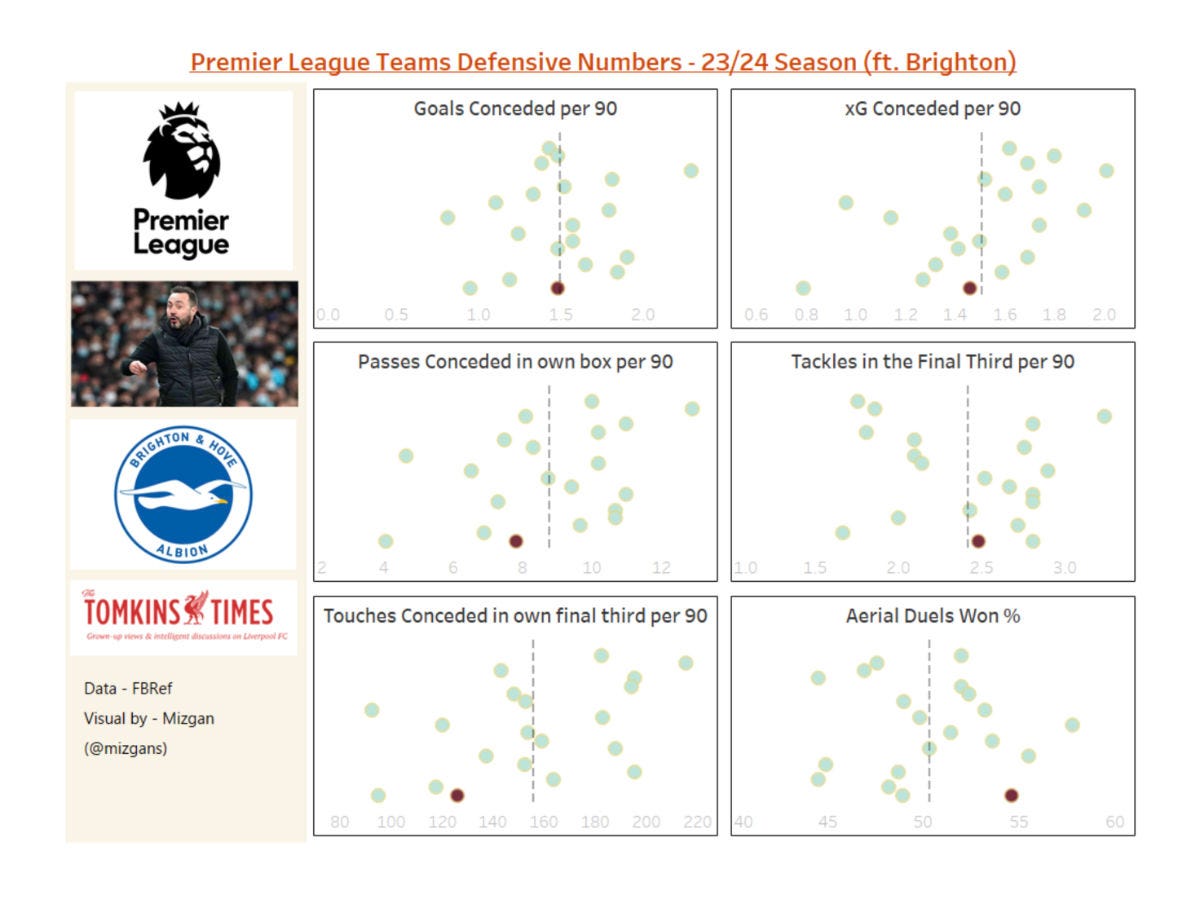

Brighton

Despite losing key midfield players in the summer (Moises Caicedo to Chelsea and Alexis Mac Allister to Liverpool), Brighton have done well in Roberto De Zerbi’s second season in charge (we can call it second season since he arrived very early in the last campaign after Graham Potter left). The results have been a bit up-and-down, but they are still 7th in the table and won their Europa League group to avoid a play-off tie in February.

The average age number would be much lower had they not signed James Milner in the summer!

In all seriousness, De Zerbi is managing one of the youngest squads in the Premier League. For a team that is not included in the traditional “Big Six” of the league, these attacking numbers are fantastic. They are above the average line in all of the metrics. Average shot distance less than 17 yards shows puts them halfway between close-in and far-out shooters.

Just like Amorim’s Sporting and Alonso’s Leverkusen, De Zerbi’s Brighton rely on dominating possession, playing hefty amount of short passes, dominating the middle third in possession and not playing many long passes.

It is fascinating to see these managers getting linked to one job. The similarity is there in how they build attacks and try to dominate games through the midfield.

One thing that worries you about De Zerbi’s team is the leaking of goals and chances at the back. They had a similar goal concession rate under him last season too. Is it something that has got to do with how he sets his team, or is it happening because he may not have the quality of players compared to elite clubs in the division?

He managed around 120 games for Sassuolo, conceding at just over 1.5 goals per 90. At Shakhtar, the rate was close to one (although the sample size was small at 30 games). It shows that there is something within the tactical setup that does allow opposition teams to have more than a sniff. We won’t delve deeper into that. It is something worth looking though.

Bayer Leverkusen

As I write this piece, Bayer Leverkusen have beaten Darmstadt and maintained a two-point cushion at the top of the Bundesliga. With 14 games to go, they have every chance of doing an extraordinary thing and a winning a league ahead of Bayern Munich, that too in Xabi Alonso’s first full season in charge of the club.

Leverkusen have the best defensive record in Germany with only 14 goals conceded in 20 games. They are very good at controlling games through the midfield and pass the opposition to death before scoring the important goals. Alonso prefers operating with three at the back, two numbers eights, flying wing-backs and a narrow front-line.

Note: Alonso apparently adopted three at the back to help stem the flow of goals the team he inherited was conceding, and isn’t wed to any one single formation.

The Bundesliga leaders are the second-best team in the league in terms of goals scored, xG created and shots attempted. They are right up there when it comes to goals per shot (exhibiting quality of shots). With regards to the average age, Alonso is managing a fairly young side. There is experience with the likes of Granit Xhaka, Álex Grimaldo, etc, but the team, overall, is young and fighting to do something special in the club’s history.

Shot distance is also middling. Liverpool have various specialist long-range shooters and are outscoring their long-range shot xG.

This dashboard shows where Leverkusen are strong under Alonso. They like to keep the ball, play a lot of short passes, have loads of touches in the middle third to dominate teams that leads to creation of chances and a very high volume of touches in the opposition box.

I still think Alonso would make use of the long-passing talents of Virgil van Dijk, Trent Alexander-Arnold, Alexis Mac Allisters and others, but maybe also work more on shorter play. He would have more variety at Liverpool than at Leverkusen. You utilise the skills of those you inherit.

The above visual shows that Alonso’s men are not lucky to be having the best defensive record in Germany. They are second-best in xG concession, best in conceding the fewest passes into their own box and second-best in allowing fewest touches in own final third.

They are aerially strong, and do make a lot of tackles in the final third (best in the league in total high-turnovers so far: 208, 10.94 per game).

Being strong aerially (Liverpool are strongest in the Premier League) and making lots of high turnovers certainly fits the Liverpool DNA.

Indeed, I’d worry about a new manager not realising how important aerial domination is in the Premier League, but Alonso knows all about that, as a player and as a manager, it seems. It’s not everything, but one important area where underdogs can bully you if you’re not big and strong enough (as I said when Klopp inherited a team of small players with no aerial dominance at all).

It also helps at set-pieces at both ends.

Finally, Mizgan runs some radar comparisons on the data. Obviously the relative strengths of the leagues is hard to factor in.

How the three contenders match up vs Klopp’s Liverpool 2.0?

This section contains three comparative radar plots comparing numbers of the three managers in contention of the Liverpool job and Klopp’s latest team version 2.0. We will just look at the league numbers and get an idea rather than making conclusive judgements.

Klopp’s Liverpool 2.0 are only better in two metrics than Alonso’s Leverkusen - PPDA and shots per 90. Now, the numbers do not tell all of the story as the Reds are also leading their league. But, it does give us an idea of the job Xabi is doing in Germany. As we saw in the dashboards above, his team are deservedly top of the Bundesliga.

This radar shows why Amorim’s name has been linked with the Liverpool job as well. His team are leading the league as well and are at par with Klopp’s 2023/24 team in most metrics.

Of course, Liverpool’s overall numbers are much better than De Zerbi’s Brighton. Although I won’t make a conclusive judgement on the latter’s chances of becoming the manager at Anfield, the underlying and in-depth numbers do not add up well for him (but the Brighton budget is small for a Premier League team).

Mizgan’s conclusion:

Numbers says Xabi Alonso. History says Xabi Alonso. Overriding senses say Xabi Alonso. But, Amorim has done an excellent job to deserve a mention too!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Tomkins Times - Main Hub to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.